Michael Buchanan,Social affairs correspondent and

Adam Eley,BBC News

Family handout

Family handoutDozens of patients were put at risk after two of the UK’s leading transplant centres continued fitting a heart device – despite knowing of concerns it had a higher mortality rate than its rival product.

Concerns were raised by the NHS about the device in 2018. Of the patients who were subsequently fitted with the mechanical pump, half went on to die within three years.

The mother of Greg Marshall – one of the patients who received the device after concerns were known and who subsequently died – told us she was “disgusted and appalled”.

The BBC has also learned that leading cardiologists at both hospitals were paid consultants for the device’s manufacturer. The hospitals were aware of this.

Both hospitals – the Freeman in Newcastle and Harefield in London – continued to use the pump for years, and questioned the reliability of the data flagged by the NHS. The pump’s manufacturer, Medtronic, eventually withdrew it on safety grounds.

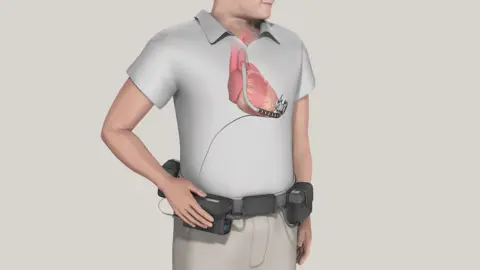

Patients with a weakened heart, who may be waiting for a transplant or deemed not suitable for one, can be offered a machine called an LVAD, a Left Ventricular Assist Device. It helps the heart pump blood around the body and, for many patients, this is their only chance of survival until a transplant becomes available.

The device is implanted into the heart, with an external wire coming out of the body – usually at the abdomen – that connects to a controller and external batteries.

LVADs have been life-savers for decades and, for a number of years, hospitals had a choice of two devices – the HeartWare HVAD, sold by the Irish-American company Medtronic, and the Heartmate III, sold by US manufacturer Abbott.

Medtronic

MedtronicIn October 2018, NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT), which oversees transplants in the UK, conducted a preliminary audit comparing how the two pumps had performed. A more detailed analysis followed in April 2019.

The results were stark. Of the 119 patients who had received the Medtronic device, 45% – or 54 patients – had died within two years. In contrast, just 15% – 15 out of 97 patients – who were given the Abbott pump had died over the same period. Similarly, the number of complications – such as strokes or needing a new pump – were significantly higher for the Medtronic device. The audit said there were “no significant differences” between the types of patients who received each device.

One of the UK’s six transplant centres, the Royal Papworth Hospital in Cambridge, did not wait for the NHS analysis. It had picked up on the growing international concerns and had stopped using the Medtronic device in February 2018 “after considering the results of two randomised controlled trials”, as their clinicians “considered the Heartmate III as superior”.

However, Harefield Hospital continued to solely use the Medtronic device until early 2021, shortly after the manufacturer had issued a safety notice. The Freeman Hospital continued until June 2021, when the manufacturer withdrew it from sale “in the interest of patient safety”.

The regulator, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), continued to approve the device for use after the 2019 analysis, though it had not been informed by the NHS of the data’s existence.

Throughout this time, patients fitted with the Medtronic device continued to die at a higher rate than those with the Abbott device.

Between October 2018, when the first set of NHS data was produced, and June 2021, when Medtronic discontinued its pump, the mortality rate of the Medtronic device was two-and-a-half times higher than the Abbott device, figures released under the Freedom of Information Act show.

Forty-nine percent of those who received the Medtronic device (39 of 80 patients) in that time died within three years. By comparison, 19% of recipients of the Abbott device (20 of 106 patients) died during the same timeframe.

Family handout

Family handoutMedtronic decided to withdraw the device in June 2021 after growing evidence that its pump had a higher frequency of strokes and deaths compared with other devices. It also cited a specific malfunction where pumps would experience a delay or fail to restart after they were stopped.

Greg Marshall was one of the patients fitted with the Medtronic device, unaware of the studies about its effectiveness compared with the rival product. A fit and healthy young man, he had ambitions of joining the Royal Marines but he suffered acute heart failure in 2019.

“It was a massive shock to us all,” his mother Tessa Marshall remembers.

By June of that year, Greg was offered the Medtronic device by the Freeman Hospital, several months after the first set of NHS data was known about.

His family say they were not presented with the long-term risks associated with the device, though an existing patient was brought in to tell them of its benefits.

Greg agreed to the surgery, but a significant complication in theatre – which the family say was never fully explained to them – led to a stroke. Greg lost movement down the left-hand side of his body, and his speech was significantly impaired.

Over time, his health slowly began to recover, but a year later, in July 2020, the heart device suddenly stopped working. When he tried to restart it, it failed to switch back on.

“The pump was not pumping, and he just slowly went blue,” Tessa says.

Greg was rushed to hospital, but the device could not be fixed. He was told he could have it removed, but, terrified of having another stroke, he refused the surgery.

The broken device remained inside him, switched off, as his heart continued to function for a further three years, during which time he was on a transplant waiting list.

In September 2023, while in hospital, he unexpectedly went into cardiac arrest. By the time Tessa had reached the Freeman, Greg had died aged 26.

His family, devastated by his loss, say they want answers.

“We said ‘Look, Greg, this is the only option you’ve got, you have got to go with it,'” said Tessa. “I kick myself now, for not doing any more research.”

Three patients may have died of this failure, the NHS Trust in Newcastle told the Department of Health and Social Care in a letter seen by the BBC.

The trust has since told the BBC the issue of the device failing to restart in patients first came to light in December 2020 – five months after Greg encountered the issue – when Medtronic published a safety notice.

ISHLT

ISHLTHospital documents show Greg’s responsible health professional was Prof Stephan Schueler, who until recently was head of the Freeman’s cardiothoracic department. Described by a former colleague as “king of the castle” in the transplant unit, Prof Schueler had a decade-long relationship with the manufacturer of the Medtronic device, public records show.

Greg’s family say he did not declare to them his financial relationship with the heart device’s manufacturer, despite such a disclosure being a requirement of the doctor’s regulator, the General Medical Council (GMC).

In a statement to the BBC, Prof Schueler said that “there was never a financial incentive nor any salary arrangements with Medtronic for me or anybody else in our team to choose one device over the other”. He did not respond to a direct question about what he had told Greg Marshall about his relationship with Medtronic but said that he “always worked within GMC standards for good medical practice” and that consenting patients for a procedure was “carried out by a whole team of specialised colleagues”.

It is common for clinicians to work as consultants for medical manufacturer and pharmaceutical companies. Such arrangements are recognised as being mutually beneficial and can lead to better outcomes for patients, though there are rules around what medics need to declare to patients.

The Freeman said in a statement to the BBC that it offered its “sincere condolences” to Greg’s family and it was investigating his case.

It said that, although it was “aware” of the NHS data in April 2019, it felt its scientific value was not reliable, and pointed out that it was not accepted in any national or international scientific publication. It said there were other publications at that time which indicated “excellent outcomes” for the Medtronic device.

Robbie Burns, a patient representative with NHS Blood and Transplant, obtained many of the documents relating to the hospitals’ continued use of the Medtronic device. He believes there should be an external investigation into how it was allowed to happen.

“It was entirely preventable,” he said.

“If I had been in the position of receiving this [Medtronic] device, and looked back at the data, I would be going, ‘Why on earth did you do this?'”

Prof Schueler said the Medtronic device had several benefits, including being more suitable for children and small adults. He said the decision to continue using the pump was taken after internal discussions had considered all the risk and benefits carefully.

Another doctor, André Simon, the director of heart and lung transplantation and ventricular assist devices at Harefield Hospital, had a similarly long-standing relationship with HeartWare and Medtronic, going back to 2014.

The man who replaced him at the hospital on the edge of west London, Dr John Dunning, told the BBC that Harefield had continued to use the Medtronic device as “it was the preference” of his predecessor.

Dr Simon, who no longer works at the hospital, did not respond to the BBC’s questions. In its statement, the Harefield said it was “aware” of his work for Medtronic and that this had been declared in multiple papers. The hospital added that he was one of a number of senior people “involved” in choosing which devices were used, and that “the continued use of the [Medtronic device] had collective support of clinicians at Harefield” until the manufacturer issued a safety notice in early 2021.

In separate statements to the BBC, both the Freeman and Harefield hospitals said their decisions to continue using the Medtronic device were based on “complex clinical decisions” and stressed that there were “no clear grounds” at the time to believe the Medtronic device was significantly inferior to the Abbott device.

Harefield said it commissioned an external review of its services in 2019 from the then-chair of the NHSBT’s Cardiothoracic Advisory Group, and this made no comment on its selection of devices.

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: BBC