Branwen JeffreysEducation Editor

BBC

BBCOfsted’s new ‘traffic light’ rating system for schools across England came into force this week – but does it mark meaningful change or, as one expert argues, “high level tinkering”?

Listen to Branwen reading this article

When Nick Green quit teaching after 17 years, one factor drove him above all others: to never go through another Ofsted inspection.

“I got out to avoid the vile process,” says Nick, 63, who was a primary school teacher and head teacher in Derbyshire. “I saw teachers become different, unlikeable people with Ofsted; I saw them cry, shout and hide in toilets. It was horrific.”

Inspections of his own schools were, he says, mostly positive – the majority received “outstanding” ratings and he never had one that was ranked below “good”.

But even so, he says that he felt weighed down by “the feeling that your career was on the line” if a judgement went the wrong way.

The same, he adds, was true of colleagues across the country.

Nick Green

Nick GreenNick, who is 63, is retired now, having worked until recently as a senior lecturer in education, and contacted Your Voice, Your BBC News to share his story. He joins a line of teachers, head teachers and education unions that have criticised Ofsted’s past inspection methods – often on account of the blunt rating system: “outstanding”, “good”, “requires improvement” or “inadequate”.

Only now, everything has changed.

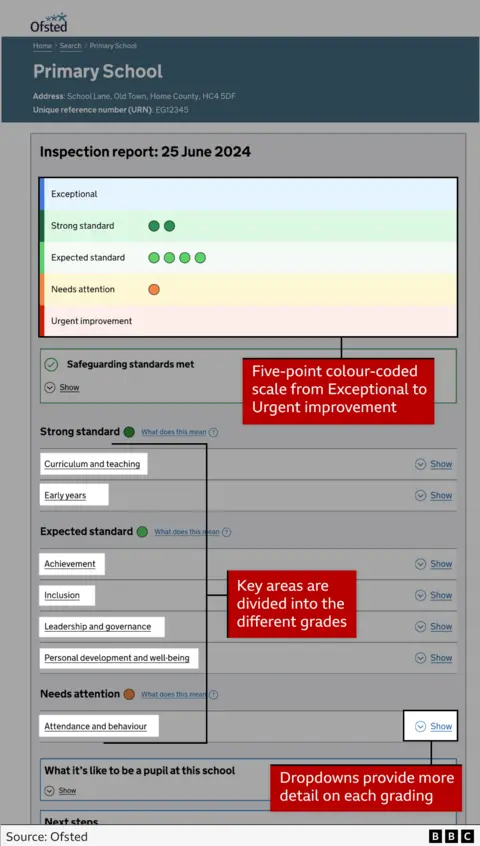

From this week, those old rankings – which were scrapped last year – have been replaced with new colour-coded report cards with more detail. Some call them a “traffic light system”; critics have likened them to Nando’s spice cards.

Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson is firm that they will provide parents with “rich, granular insight”. But not everyone is convinced.

A letter signed by more than 30 people – including the leaders of four teaching unions in England – warns the new system will “continue to have a detrimental impact on the wellbeing of education staff and hence on students’ school experience”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT), which mainly represents primary head teachers, has said it will ballot on whether to take strike action over the new system in England.

But some inspectors are reported to be concerned by the changes for entirely different reasons.

One whistleblower told a newspaper last year that Ofsted was “bending over backwards” to make inspections less stressful – at pupils’ expense.

Whatever side of the argument you sit on, the sheer vigorousness of the debate prompts the question: what really is the most effective method of assessing a school – and are we thinking about how to rate them in entirely the wrong way?

The tragedy that sparked calls for change

It was a tragedy involving one head teacher that was a catalyst in bringing this system under the spotlight.

Ruth Perry had been the head of Caversham Primary School in Reading for more than a decade when Ofsted inspectors arrived in November 2022.

Afterwards she learned they had decided to downgrade the school from outstanding to inadequate, the lowest grade.

Two months after the inspection, Mrs Perry died by suicide.

A coroner later ruled an Ofsted inspection had contributed to her death – and issued a report calling for changes.

PA Wire

PA WireFor over three decades, Ofsted – the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills – has inspected schools, colleges, nurseries and childminders across England.

In Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland inspections are carried out by separate bodies entirely, with their own methods.

There had long been criticisms of the Ofsted system, including from within the teaching profession, about the pressure inspections brought and how useful they were.

In the report calling for changes following Mrs Perry’s death, system-wide issues were highlighted – and the possibility a school could be judged “inadequate” despite being good in almost every respect was raised.

In the wake of an independent study commissioned by Ofsted, its chief inspector Martyn Oliver promised “real change”.

An all-party group of MPs later echoed the call for one- or two-word judgements to go. Mrs Perry’s sister, Julia Waters, has also campaigned for those judgements to be scrapped.

The question, now that change has arrived, is how the new system will work in practice.

Traffic light scale unpacked

Under the new “traffic light system”, Ofsted inspectors will use a five-point grading system, ranging from “urgent improvement” to “exceptional” to assess six areas of school performance. (On keeping children safe, the standard will be rated as “met” or “not met”.)

Reports will also take into account more about the context of a school, such as whether familes are struggling on low incomes. Plus, it will be possible for an inspection to be paused if there are concerns about the wellbeing of the headteacher.

This new framework will be fairer to schools, colleges and nurseries, Ofsted argues, by recognising all of their strengths without a single-word judgement.

“Our new approach will help raise standards for children, particularly those who are disadvantaged or vulnerable,” a spokesperson added.

“Our new report cards will give parents a clearer understanding of a school’s strengths and areas for improvement, helping them make more informed decisions about their child’s education and care.”

But it’s not yet fully clear how the new system will work in practice – even though it came into effect earlier this week.

And an independent review of the system, commissioned by Ofsted, said: “There is a wide consensus that the significant increase in formal judgement areas will result in “many more ways to fail’.”

Some smaller rural schools are worried about how they will manage the paperwork.

Three unions attempted to challenge the new system in court; on 3 November, their challenge was defeated.

Though a year ago Julia Waters welcomed the plans to scrap the single-word judgments, now she argues the “tweaks” made by Ofsted don’t do enough to address the concerns that followed her sister’s death around head teachers’ well-being.

Others, including some teachers, take a sharply different perspective. Chris McGovern, chairman of the Campaign for Real Education and a former head teacher and school inspector, argues that the benefits for children and parents “far outweighs” the pressure on schools.

”The overriding matter of importance with regard to school inspection is: ’What is in the best interests of the children?’

“Inspection is in their best interests because above all else it is about ‘quality control’.”

A baked-in part of parenting

When Ofsted was introduced in 1992, it “had a huge impact”, says Colin Diamond, professor of educational leadership at the University of Birmingham.

He trained as an Ofsted inspector during the 1990s and says that when school inspections were carried out by local education authorities – as they previously had been – there was “huge variation” in how they were conducted.

In the years since, browsing reports produced by Ofsted – as well as those from Education Scotland; Estyn in Wales; and the Northern Irish inspectorate, plus the Independent Schools Inspectorate – has become a baked-in part of how parents choose schools.

In a YouGov survey of 1,090 parents, commissioned by Ofsted, seven out of 10 said they preferred the new-look report cards to Ofsted’s old inspection reports.

Those I spoke to, however, were rather more mixed.

“I’m in two minds,” admits Jennifer Harris, a solicitor from Peterborough, who has two children. “[That’s] because I know it does put a lot of pressure on the schools and on the teachers.”

Her 10-year-old daughter will start secondary school next year – but all the secondaries in her area were rated “good”. While she doesn’t have much use for one-word ratings, she does think there is some value in Ofsted’s inspections.

“I do think they have their place because I think you need all those different bits of information to put together yourself to build up a picture.”

Jennifer Harris

Jennifer HarrisBut John Jerrim, professor of education and social statistics at University College London, cautions against putting too much weight on any single report.

He and other researchers have studied the consistency and reliability of inspection reports and suggest the relationship between an Ofsted grade and exam outcomes and future earnings is weaker than commonly assumed. Their research was conducted under the previous inspection framework.

The average “time lag” between inspections can also be too great to provide a reliable snapshot of a school’s performance, Prof Jerrim argues, plus he believes that the seniority of inspectors can make a difference to the result of the inspection.

“They’re trained professionals, they’re experts, they know what they’re looking for,” he says, “but at the end of the day, it does come down to some kind of individual judgement.”

However, the Campaign for Real Education’s Chris McGovern warns inspectors should not be “demonised”.

Most, he says, “are thoughtful, considerate and kind”.

Meaningful reform or ‘tinkering’?

What’s happening in England isn’t entirely new. Elsewhere across the UK, inspectors have also moved beyond single-word judgements.

In Wales, Estyn has removed judgements such as “excellent” and “good” from reports, instead summarising findings by highlighting a school’s strengths and areas for improvement.

Meanwhile, the body that inspects Church of England schools and academies has similarly shifted away from gradings. In 2023, it scrapped its four rankings of “excellent”, “good”, “requires improvement” and “ineffective”.

But the new Ofsted framework will be a big change for parents in England.

Ofsted/PA Wire

Ofsted/PA WireParents often want to know more than Ofsted reports tell them – for instance, whether a school will match their child’s individual interests or how welcoming it feels.

The London borough of Camden recently introduced a more descriptive school report card, which provides a link to each school’s Ofsted report, as well as some official statistics about other matters such as pupils’ wellbeing and anti-bullying policies. It also includes photos and a summary of the school’s values.

Other areas have said they will consider something similar.

But for Jennifer Harris, it was something far more low tech that ultimately helped her choose the secondary that was the best fit for her children.

“The biggest factor was the open day,” she says, “and going to the school and listening to the head teacher talk about his vision.”

PA Wire

PA WireUltimately, though, the new Ofsted system will take time to settle in – and reaching a verdict on it will take time too.

For now, though, Ofsted is confident that this is the way to help deliver best possible results for children. And the Department for Education adds that it is determined to deliver a brilliant education for every child by “shining a light on what’s working and driving change”.

What remains to be seen is whether it’s enough. On this front, Prof Diamond is sceptical. “What I think we’re seeing here is – forgive the phrase – high-level tinkering.”

It will take months, perhaps years, for parents to decide for themselves whether or not they think he’s right.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how.

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: BBC