The path leading from Edmond Halley’s writings on magnetism to UFOs under Brazil is as convoluted as you might expect. Nonetheless, it was Halley – best known for using Newtonian mechanics to predict the return of the comet now bearing his name – who introduced the hypothesis that Earth is hollow and filled with increasingly small spheres. He also suggested that these spheres are habitable.

Halley’s hypothesis, introduced to the Royal Society in November 1691 and published in its Philosophical Transactions the following year, has enjoyed a long, outlandish career. Alleged occupants of Earth’s interior have since included mammoths, super-civilisations, and the aforementioned UFOs. Kept alive in scientific treatises of an increasingly disreputable character, the ‘Hollow-Earth Theory’ has constantly been reinvented in fiction, too. Novelists and fringe thinkers alike have found fruitful its capacity to unsettle comfortable assumptions about the world we inhabit.

Although he warned fellow philosophers that the hypothesis he had ‘stumbled’ upon may at first appear ‘Extravagant or Romantick’, Halley’s concept was actually quite grounded, or at least practically minded. Inexplicable variations in the movements of compass needles had long frustrated navigators and hampered commerce. Halley explained these anomalies by supposing that Earth’s North and South Poles are accompanied by two additional magnetic poles, rotating at a slightly different pace to the known ones. No such poles exist on the surface, but they could, perhaps, belong to a free-spinning sphere inside Earth. Halley cited Saturn, where gravity holds both planet and rings firmly in place, as an analogy: just as Saturn’s rings spin around the planet proper, Earth’s magnetic core might rotate in concert with its outer crust (rather than ricochet around inside).

More radically, Halley suggested this core might, in turn, be surrounded by additional spheres, nested like matryoshka dolls, housing living beings. Such economical use of Earth’s interior as habitable land was an idea befitting widespread notions of divine wisdom. Inner beings might even enjoy light from ‘peculiar Luminaries’ that Halley analogised to those that illuminate the underworld in Virgil’s Aeneid. In 1716 he guardedly suggested that these luminaries sometimes gush from Earth’s bowels into the night sky as the aurora borealis.

Underground worlds were no innovation of Halley’s, but his fusion of habitable spheres, the aurora, and the mysteries of magnetism provided a newly coherent recipe for subterranean speculations. This ‘Romantick’ hypothesis intrigued intellectual communities across the world, even if it was rarely found convincing. Writing in The Christian Philosopher (1721), Puritan clergyman Cotton Mather, resident of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, discussed Halley’s spectacular conjectures with interest. Perhaps fearing that they were a little too spectacular, he concluded that ‘it’s time to stop, we are got beyond Human Penetration’.

Down the Symmes Hole

It was long after Halley’s death that his hypothesis found its most dedicated proponent: the trader and former US army officer John Cleves Symmes Jr. In a circular distributed from St. Louis in April 1818 – and addressed ‘TO ALL THE WORLD!’ – Symmes pronounced that ‘the earth is hollow, and habitable within; containing a number of solid concentrick spheres’. Unlike Halley, he intended to take a look at them.

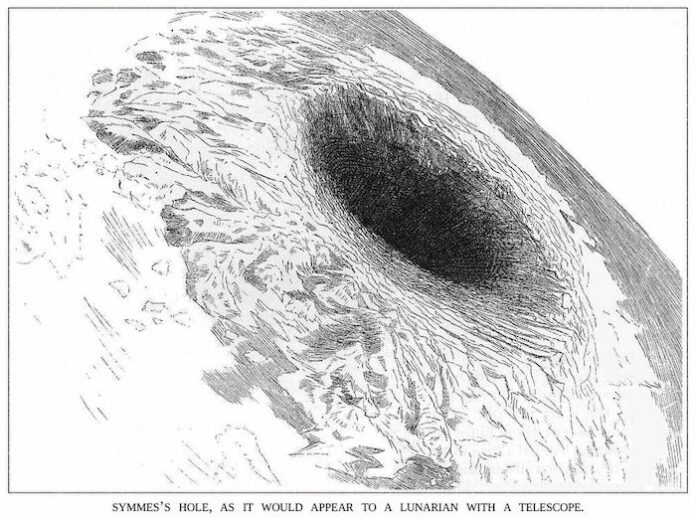

This would be possible because Symmes, who insisted that he had encountered Halley’s work after coming up with the idea himself, added new features: gigantic holes at the North and South Poles through which the inner spheres can be entered. Calling (in vain) upon the savants Humphry Davy and Alexander von Humboldt for support, Symmes proposed to lead a hundred-strong expedition from Siberia in search of the northern hole. By this period, Halley’s suggestion had drifted outside scientific plausibility, but, given that Earth’s poles were hardly less mysterious than its interior, Symmes’ idea could not be dismissed as hopelessly impossible.

Symmes, a man of no formal scientific training, combined a democratic attitude towards knowledge-making with a practicality that thrived in the young American republic. As such, his circular gestured to the opportunity for territorial expansion. Symmes was well known for his lectures in Cincinnati, Ohio, a state substantially formed from territory purchased by his uncle and namesake, John Cleves Symmes, in 1788; more recently, in 1803, the US had gained vast lands from France through the Louisiana Purchase. Symmes hinted that yet more land awaited US settlers in the (hypothetically) temperate inner world.

Despite the support of several prominent Ohio figures, Symmes’ petitions to Congress, and thus his expedition, did not get off the ground – let alone underneath it. He died in May 1829, aged just 48. In the 1870s Symmes’ son, the farmer Americus Vespucius Symmes, spearheaded a revival of Hollow-Earth Theory after decades of dormancy. And, thanks to renewed media coverage, ‘Symmes Holes’ were becoming bigger than ever.

Hollow fictions

One result was a swell of Symmesian fiction. The topsy-turvy inner world especially suited a new wave of utopian and dystopian novels, where surface rules were turned on their heads. The seeds had been planted back in 1820 with the pseudonymously written Symzonia, a Swiftian satire in which a patriotic American traveller to Earth’s interior learns of his vast inferiority to the native ‘Internals’. The Symmes revival saw some of the era’s most pressing social issues crammed inside the Hollow Earth. In Mizora (1880), by Ohio schoolteacher Mary E. Bradley Lane, the protagonist is sucked into a Symmes Hole; within, she encounters an advanced matriarchal society. Pantaletta by William Mill Butler (1882), set in the inner world of ‘Petticotia’, where women cruelly rule over men, provided a reactionary alternative.

Copycats who took the theory seriously also emerged. These professedly independent-minded thinkers – often businessmen, such as Connecticut merchant Franklin Titus Ives – admitted as few intellectual debts to Symmes as Symmes had to Halley. At a time when scientists could not agree whether Earth’s core was liquid or solid, there were tantalising and convenient unknowns for these authors to exploit. In 1892 the respected British geologist Charles Lapworth even wondered if, ‘as others have suggested’, Earth is ‘a hollow shell, or series of concentric shells’. Most Hollow-Earthers dropped Halley’s concentric shells, however, leaving behind a simpler, and hollower, Hollow Earth.

The tone of these writings is not always transparent. Some were earnest, many self-avowed fiction, but others were hard to classify. Washington L. Tower’s Interior World (1885), for example, combined children’s adventure story with an exposition of Hollow-Earth physics. ‘How much of the book is to be taken seriously’, mused a reviewer of another puzzling work, Ives’ The Hollow Earth (1904), ‘Mr. Ives does not say’.

What lies beneath?

The attainment of the poles in the early 20th century dampened hopes that any Symmes Holes would be found. At the same time, Hollow-Earth Theory shot to new (fictive) fame in the ‘Pellucidar’ stories of Edgar Rice Burroughs, beginning with At the Earth’s Core (1914). The prehistoric monsters surviving in the inner world of Pellucidar – cavemen, dinosaurs, sabre-toothed cats – kept Burroughs’ virile protagonists, including Tarzan, busy for decades.

It was science fiction that heralded the Hollow Earth’s next evolution. Between 1945 and 1948 Amazing Stories – the founder of which, Hugo Gernsback, coined the term ‘scientifiction’ – boosted circulation with the ‘Shaver Mystery’, an alarming series of stories describing an underground world populated by malignant aliens. Neither their mysterious author, Richard S. Shaver, nor the magazine’s conspiratorial editor, Raymond Palmer, would confirm that these stories were mere fiction. And perhaps, it soon appeared, they were not. The first known UFO was spotted in 1947, flying over Washington state; by the 1950s, these uncanny objects were seen coming not down from outer space, but up from caverns beneath Brazil.

In a December 1959 issue of Flying Saucers, Palmer’s latest publishing venture, he confirmed what he and Shaver had previously hinted: that UFOs are denizens of the Hollow Earth, entering and exiting via Symmes Holes. His source was a garbled account of a US pilot who had entered one of these holes, encountering lush vegetation and even a mammoth. In 1961 yet another Palmer periodical, The Hidden World, reprinted Shaver’s stories of subterranean menace as pure fact. Now the Hollow Earth, once a bounteous zone for colonial expansion, seemed a rather dangerous region to find under one’s feet.

In the centuries after Halley aired his logical speculations, Hollow-Earth Theory was kept alive by thinkers with ever-diminishing respect for established expertise. Many were unruly and self-confident assailers of the scientific status quo, but even the unconverted found Earth’s depths a place of symbolic power. The hollow interior was a useful space in which to put objects of fear and desire that had no place anywhere else on Earth.

Richard Fallon is Research Associate in Natural History Humanities at the University of Cambridge. Patricia Fara will return next year.

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: historytoday.com