In July 1975, director Martin Scorsese went to the Greenwich Village club The Bottom Line to watch Bruce Springsteen play what would become a legendary five-night, 10-show stint.

At one point, Springsteen, who was still evolving from a halfway decent frontman to rock ’n’ roll’s live dynamo, cued growing applause from the crowd with his back to them — then looked over his shoulder and said, “You talkin’ to me? Are you talkin’ to me?”

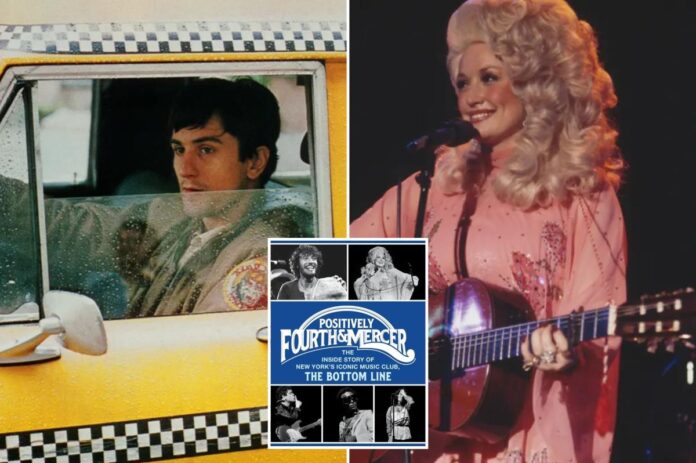

The following year, Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver” hit theaters with Springsteen’s words allegedly providing one of the film’s most iconic moments.

“The movie comes out not too long after, and there’s [Robert] De Niro saying that line,” Jon Landau, who became Springsteen’s manager not long, recalls in the new oral history, “Positively Fourth and Mercer: The Inside Story of New York’s Iconic Music Club, The Bottom Line,” by club co-owner Allan Pepper and journalist Billy Altman.

“An oasis of purity for the serious music fan,” the Bottom Line hosted virtually every form of music during its 1974-2004 run and, especially during its early years, saw countless indelible, even incendiary rock ’n’ roll moments.

In December of 1975, Patti Smith played a three-night stint there just one month after the release of her legendary debut album, “Horses.”

The Bottom Line’s owners had taken great care and expense to ensure that the club had the best sound system possible. But Smith, known as the godmother of punk rock for a reason, did not care.

“At one show Patti did a tap dance on the grand piano,” stage manager Marc Silag recalls in the book. “The next show she took a guitar and stuck the neck through one of our stage monitors. After the show, I carried it backstage and said to her, ‘What am I going to do with this tomorrow night?’ and the band just pushed me out of the dressing room.”

Ornery rock stars became a theme in the 1970s.

Lou Reed was a frequent performer at The Bottom Line despite a knack for inspiring fights in — and with — the audience.

“Every time Lou played the club, there were fights,” says waitress Donna Diken in the book.

“One time, he kicked a glass that I guess had liquor in it into the audience,” adds Pepper. “It splashed on two guys who got very offended and wanted to go backstage and confront him, and my guys stopped him. The conflict elevated, and one of the men wound up getting arrested.”

Another time, Reed and his band refused to go on because he felt the club’s owners didn’t respect him.

“And when they asked what they could do to show their respect,” recalls club host Jack Leitenberg, “Lou suggested a bottle of Jack Daniel’s.”

Miles Davis was another artist who gave the club’s management fits.

At one show in the mid-’70s, the jazz legend kept the crowd waiting 40 minutes past the scheduled time for his second set. Getting nervous — because Davis had previously bailed on second sets at The Bottom Line — Pepper went to retrieve the trumpeter but was stopped by Davis’ road manager, Jim Rose.

“I’m about to go into his dressing room when Jim Rose steps in front of me and says, ‘Listen, you can’t go in right now,’” Pepper recalls in the book. “I say, ‘Why not?’ and he says, ‘Cause’s he’s getting [oral sex]. He’ll be out soon.’ Apparently, they’d brought a hooker in to service him before the show. That was Miles.”

There were more wholesome memorable moments, too, like during Dolly Parton first solo performance in New York City, in 1977.

It was her first time having to charm a cynical Manhattan crowd, with the likes of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards and the original cast of “Saturday Night Live” in attendance.

In the middle of her first song, Parton’s fake nail broke off while she was playing her guitar.

“Well, goodness sake, you know what? I learned to play the G [chord] with my nails on, but OK,” she told the crowd. “I just can’t do it like this. Hold on.”

And with New York hipster royalty staring at her, she removed her remaining nails — all nine of them.

“And everyone goes crazy,” recalls theater publicist Judy Jacksina, who was in the crowd that night. “It was thunderous applause all the way through. She knew how to play an audience. She didn’t care who was out there. It was genius.”

And when blues legend Muddy Waters played, Bob Dylan showed up hoping to sit in.

Silag, the stage manager, went out between songs to tell Waters, who replied that he’d bring the singer up after the following song.

But when the time came, the blues legend got confused.

“Ladies and gentleman, we’ve got a friend who’s gonna come up and sit in with us,” said Waters. “Give him a big hand — Bob Denver!”

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: nypost.com