In the year 1977, a young advertising professional trekked to Upper Dachigam near Kashmir — the route winds through rugged, alpine meadows — all in an attempt to spot the hangul, a flagship stag species endemic to the region. He penned his experiences down, which later made it to a full-page feature in The Indian Express.

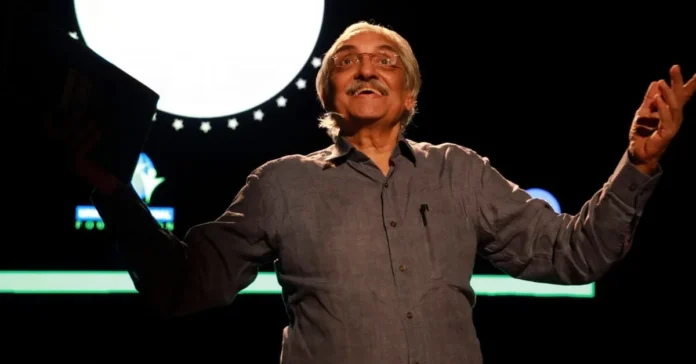

Looking back, the boy would recall the incident as shaping two of his life’s leitmotifs — Bittu Sahgal is now a veteran journalist with four decades of advocacy in conservation. He’s hailed for his prowess in environmental activism, wielding the pen as powerfully as he champions causes on the ground.

And his brainchild, wildlife magazine Sanctuary Asia, is an article of faith for those who look to journalism to shape the future of conservation. The story of how the magazine was born in 1981 is as iconic as the ones that have filled its pages in the last 44 years.

One evening, while sitting around a campfire at Ranthambore, Sahgal asked his mentor Fateh Singh Rathore (often described as the founding father of Ranthambore National Park) a simple question: What can I do to save the tiger?

Rathore responded, “Bittu, there are hundreds of bekaar (useless) magazines on Indian politics, sports, films… but not one wildlife magazine. Start one! Win public support. That will help. But you are a Bombaiya, city-bred, I know you will do nothing! Then, on your next visit, you will ask the same question. You city people are like that only.”

“Exactly nine months later, in October 1981, I handed him the inaugural issue of Sanctuary Asia,” Sahgal shares. Ever since its first edition, the magazine hasn’t wavered from its moral compass — “without having missed a single issue despite wars, social strife, and economic meltdowns” — never deflecting from speaking truth to power, amplifying the voices of marginalised communities and ensuring every species gets its moment in the sun.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2026/02/02/bittu-sahgal-5-2026-02-02-18-08-34.jpg)

Every alternate issue of the monthly magazine is dedicated to young readers (Sanctuary Cub). Then, in 2015, Sanctuary Nature Foundation was established as an extension of the same vision, bringing together conservationists, naturalists, photographers, writers, and editors to impact change on the frontlines.

An afternoon chat with Bittu Sahgal

It’s sufficient to say that few manage to summon the kind of alchemy Sahgal brings to the topic of conservation.

His life, he says, has been a mosaic of inflection points. His earliest memories of the wild are rooted in his growing-up days in Shimla, as he ardently watched monkeys and admired the forests that lay just beyond the boundary wall of the Bishop Cotton School where he was studying. Later in life, his friendship with Fateh Singh Rathore, among others, strengthened his resolve to protect the wild.

Recalling one anecdote from those years, Sahgal shares, “We had just finished dinner and were sitting around the fire at Ranthambore when I heard a scuffle behind me. Fateh shone his powerful torch, and it fell on dragmarks and a pool of blood. We discovered a young sambar fawn had been killed by a leopard just feet away from where we sat, and we hadn’t realised a thing.”

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2026/02/02/bittu-sahgal-2026-02-02-17-56-18.jpg)

Sahgal is a living archive of these stories — events, and incidents that deepened his awe towards the wild. But the one that transformed the love into a deeper calling was when he came across the carcass of a tiger that had been poisoned. “I thought to myself, nature already hands these creatures so many trials in their lives, and as humans, we just add to these trials,” he shares.

Driving conservation through conversation

Despite this being my first interaction with Sahgal, there’s a semblance of familiarity. His name has featured across my interviews with conservationists, wildlife activists, and even homestay owners who’ve enjoyed a visit from him.

The quest to be Sahgal-approved is real. When I tell him this, he laughs. While ‘Sahgal, the conservationist’ is well known, few know about ‘Sahgal, the salesman’. I didn’t either until we backtracked into his youth.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2026/02/02/bittu-sahgal-6-2026-02-02-18-18-32.jpg)

“From calendars to posters to huge polythene buckets for the chemical industry, I sold everything as a teenager in Kolkata,” he shares. These gigs were undertaken by day between 10 am and 6 pm; between 6 am and 9 am, he attended his BCom lectures at St. Xavier’s College. His salesman’s instinct and experience taught him an important lesson. “You can’t walk into a room and sell a guy something that he doesn’t really need.”

Now, Sahgal contextualises this learning — “people need to be convinced that it is in their best interest to save the biosphere, the forests, wetlands, grasslands, rivers and oceans. I’m still a salesman. A salesman for nature,” he beams.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2026/02/02/bittu-sahgal-3-2026-02-02-18-02-32.jpg)

There wasn’t a direct segue from sales to journalism. The years in between were filled with chartered accountancy, advertising, and more. But the perks and pay paled in comparison to the satisfaction Sahgal drew from his time in the wild. The only thing that could come close to it was the pleasure of writing about these experiences. And thus started Sanctuary Asia.

Effecting policy shifts through journalism

In 1989, the BSES (Bombay Suburban Electric Supply) wanted to install a 500-megawatt thermal plant in Dahanu, Maharashtra. This was just a year after Dahanu had been declared a ‘Green Zone’ owing to its horticultural status. The thermal plant would impact the region’s agriculture. A 2009 study highlights Dahanu’s scale of production — over 50,000 tons of chikoos, 2,000 tons of guavas, 50,00,000 coconuts, a monthly production of 8,500 railway wagons of vegetables, 2,500 wagons of fodder, and 500 truckloads of spider lilies.

Sahgal, who had friends in the region, fighting tooth and nail against the expansion of the thermal plant in every way they could, could empathise with their pain.

In 1994, after a plea in the Bombay High Court was declined, on a request from Nergis Irani, a prominent resident of Dahanu who was the founder of the Dahanu Taluka Environmental Welfare Association (DTEWA) and leader of the long-term campaign against the plant, Sahgal approached the Supreme Court. He filed a writ petition seeking the implementation of the Dahanu ESA notification, which followed the 1991 decision to declare Dahanu taluka an Ecologically Fragile Area (EFA) under the Environment Protection Act, 1986. The aim was to curb polluting industries and regulate land use in the region.

In October 1996, the Supreme Court directed the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) to re-examine the issue and set up the Dahanu Taluka Environment Protection Authority (DTEPA).

Sahgal recalls the outcome clearly. “We went to the Supreme Court and were able to prevent the second thermal plant from coming up. We had asked for the demolition of the first one, but the court allowed it to remain, on the condition that a 10-square-kilometre protected buffer be created around it. That decision led to the idea of eco-sensitive zones.”

He commends Debi Goenka, Shailendra Yashwant and Shyam Chainani, the founding member of the Bombay Environmental Action Group, for advocating for this concept. According to Sahgal, it has since helped protect our coastal landscapes, mangroves, leopard habitats, and other vulnerable ecosystems.

Eco-sensitive zones are now protected buffer areas around national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, notified by the MoEF&CC. They regulate activities such as mining, construction, large-scale tourism, and pollution, thus helping reduce pressure on fragile landscapes while still supporting local livelihoods, including practices like organic farming.

Teaching kids to stand up for nature

But despite the impact his work was having, Sahgal says there were always naysayers. “In 1981, when I started Sanctuary Asia, 90 percent of my time was spent explaining to people why I had started a wildlife magazine when the nation had so many “real problems”.” Four decades later, protecting the biosphere and the climate crisis have become the fulcrum of virtually every other environmental debate in the country. Convincing adults was always tough. That’s where Sahgal appreciates the lack of cynicism and the pure innocence of children.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2026/02/02/bittu-sahgal-1-2026-02-02-17-58-32.jpg)

One of his favourite programmes, now part of the Sanctuary Nature Foundation, is ‘Kids for Tigers’, an adult literacy programme launched in 2000, which took environmental education to 700 schools across India through workshops, nature walks, camps, and tiger fests. “Propelled by Sunil Alagh of Britannia Industries and Prannoy Roy of NDTV, children met government officials, sports personalities, celebrities, and journalists, to convince them that protecting nature is the surest way to safeguard both present and future generations,” Sahgal shares.

This is important to Sahgal. In fact, it’s the most important thing that Sanctuary Nature Foundation does. I ask him why, and he pauses before he replies, “My generation owes your generation an apology because my generation has not looked after your world.”

All pictures courtesy Bittu Sahgal

Sources

‘A veteran environmental journalist on 40 years of writing on wildlife: Bittu Sahgal [Interview]’: by Divya Kilikar, Published on 25 March 2025.

Kids for Tigers.

‘India’s Notified Ecologically Sensitive Areas (ESAs)’: by Meenakshi Kapoor, Kanchi Kohli, Manju Menon, Published in 2009.

‘Shyam Chainani (1943-2010)’: by Bittu Sahgal, Published in August 2011.

‘Commentary: 40 years and Counting’: by Bittu Sahgal, Published in October 2021.

Office Memorandum

Restrictions on the setting up of industries in Dahanu taluka, district Thane (Maharashtra)

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: thebetterindia.com