No one can say exactly when, or if, gay men started running Silicon Valley. They seem to have dominated its upper ranks at least the past five years, maybe more. On platforms like X, the clues are there: whispers of private-island retreats, tech executives going “gay for clout,” and the suggestion that a “seed round” is not, strictly speaking, a financial term. It is an idea so taken for granted, in fact, that when I call up a well-connected hedge fund manager to ask his thoughts about what is sometimes referred to in industry circles as the “gay tech mafia,” he audibly yawns. “Of course,” he says. “This has always been the case.”

It had been the case, the hedge funder says, back in 2012, when he was raising money from a venture capitalist whose office was staffed with dozens of “attractive, strong young men,” all of whom were “under 30” and looked as though they had freshly decamped from “the high school debate club.” “They were all sleeping with each other and starting companies,” he says. And it is absolutely the case now, he adds, when gay men are running influential companies in Silicon Valley and maintain entire social calendars with scarcely a straight man, much less a woman, in sight. “Of course the gay tech mafia exists,” he continues. “This is not some Illuminati conspiracy theory. And you do not have to be gay to join. They like straight guys who sleep with them even more.”

Ever since I started covering Silicon Valley in 2017, I’ve heard variations of this rumor—that “gays,” as an AI founder named Emmett Chen-Ran has quipped, “run this joint.” On its face, a gay tech mafia seemed too dumb to warrant actual investigative inquiry. Sure, there were gay men in high places: Peter Thiel, Tim Cook, Sam Altman, Keith Rabois, the list went on. But the idea that they were operating some kind of shadowy cabal seemed born entirely of homophobia, the indulgence of which might play into the hands of conspiracy-minded conservatives like Laura Loomer, who, in 2024, tweeted that the “high tech VC world just seems to be one big, exploitative gay mafia.”

Over time, though, the rumor refused to die, eventually curdling into something closer to conventional wisdom. Last spring, at a venture capitalist’s party in Southern California, a middle-aged investor complained to me at length about how he was struggling to raise his new fund. The problem, he explained, boiled down to discrimination. I took him in as he spoke. He had the uniform down cold: a white man with a crew cut, wearing a tasteless button-down stretched over mild prosperity, and a fluent conviction that AI was, thank god, the next big thing. He looked exactly like the sort of man Silicon Valley has been built to reward. And yet here he was, insisting that the system was rigged against him. “If I were gay, I wouldn’t be having any trouble,” he said. “That’s the whole thing with Silicon Valley these days. The only way to catch a break,” he claimed, “is if you’re gay.”

Over the course of 2025, similar sentiments bubbled up on X, where Silicon Valley tech workers joked about offering “fractional vizier services to the gay elite.” Anonymous accounts hinted at an underworld of gay Silicon Valley power brokers who influenced and courted—“groomed”—aspiring entrepreneurs. At an AI conference in Los Angeles, an engineer casually referred to a top AI firm’s offices, more than once, as “twink town.”

By the fall, speculation intensified, and then a photo appeared on X of a group of Y Combinator–backed founders crowded near a sauna with Garry Tan, the incubator’s president. The image seemed innocuous enough: a few young, nerdy men in swim trunks, squinting into the camera. But almost instantly, it set off a round of viral gossip about the peculiar intimacies of venture capital culture. Not long after, a founder from Germany, Joschua Sutee, posted a photo of himself and his male cofounders—apparently naked, swaddled in bedsheets—submitted as part of what seemed to be a Y Combinator application, a move that appeared designed to court a knowingly erotic male audience. “Here I come, @ycombinator,” the caption read.

The notion that Y Combinator was grooming male entrepreneurs makes little sense—for lots of reasons, and for one in particular. “Garry is straight straight straight straight,” says a person who knows Tan. “But he believes in the benefits of the sauna.” When I ask Tan for a comment, he is blunt—some founders were over for dinner and asked to use his recently installed sauna and cold plunge. From there, Tan says, “rejects” of Y Combinator “manufactured this meme that it was somehow more than that.”

And yet, similar rumors persisted and compounded, originating as often from outsiders (sometimes with dubious political motivations) as from insiders. When I call up my longtime industry sources to get their thoughts on the gay tech mafia, not only have they heard of it—they have highly specific notions of how it works. These are credible people who believe seemingly incredible things. One San Francisco investor tells me that he believes the Thiel Fellowship is a training ground for gay industry leaders. (When I run this notion past a couple of former Thiel Fellows, they tell me they met Thiel one time at a dinner, where he appeared “slightly bored,” says one of the fellows, a straight man. “I mean, I wish Peter tried to groom me.”) Meanwhile, people’s gaydars are practically overheating. I hear, more than once, that anyone in Silicon Valley who has achieved outsize success is probably gay.

Isn’t it strange, one San Francisco–based venture capitalist muses, how a certain defense-tech executive achieved so much success at a relatively young age? “Isn’t he gay?” the VC asks. “He must be.” I tell him he is mistaken—the executive is married to a woman. “Sure,” he replies. “But have you ever seen them together?” Another entrepreneur who raised capital from two well-known gay investors tells me that he’s accustomed to fielding scrutiny about his sexual orientation. “People say I’m gay,” he says. “There’s always jokes. Like, ‘How’d you get the money, bro?’”

Then there are the anonymous X accounts amplifying allegations of misconduct. Their posts are calibrated for attention: detailed enough to suggest insider knowledge of the Valley, vague enough to invite darker interpretations. I take the bait and, one afternoon in late November, spend nearly an hour texting one such account owner over Signal who agrees to speak to me only if I keep his handle secret.

This person describes the Valley as a place known for “ecstasy, psychedelic fueled gay sex stuff.” Has he experienced any of it himself? No. But he knows people who have—people who are “pretty afraid” and “young af.” He won’t name names, won’t connect me to anyone, but he swears that any negative rumor I’ve heard about gay men in Silicon Valley is true. He suggests a conspiracy so sprawling it rivals QAnon and implicates the entire US government. He gives me vague reporting advice: “It should be easy to find. 2nd page of Google type thing.”

Finally, frustrated by his evasiveness, I ask what he thinks will happen if he tells me what he knows. “I truly believe,” he says, “killed.” Then he offers a suggestion. The only way to expose this blockbuster of a tale is “project veritas style: Take a 20 year old dude, make an X acc[ount]. Send him to the right places in SF and you’ll break the story if you go deep enough.”

The problem with conspiracy theories, even offensive ones, is that they are rarely wholly invented. They almost always arise from some fragment of truth, which imagination then contorts. The difficulty with this particular rumor is that, while I was unable to substantiate darker allegations, parts of the story still resonate. In conversations with 51 people—31 of them gay men, many of them influential investors and entrepreneurs—a portrait emerged of gay influence in Silicon Valley that is intricate, layered, and often contradictory. It is a world in which power, desire, and ambition interweave in ways both visible and unseen, a world that is, in some ways, far richer—and more complicated—than the rumors themselves suggest.

Most of the people who speak to me for this story do so on the condition that their names be kept confidential. Some of it is just garden-variety caution. “It may not be wise for me to be talking to a reporter describing all these parties,” says one, “because people would be like, Geez, why would we invite you?” Other excuses are murkier: “It’s not so safe to speak about this in too much detail,” says a founder who works in AI. “Anyone involved is an operator or a VC, and it might lead people to wonder about who is getting advantages.” Amid the deflections and whispers, though, there seems to be an unmistakable truth: Gay men are rising.

“The gays who work in tech are succeeding vastly,” an angel investor, who is a gay man, tells me. “There’s the founder group of gays who all hang out with each other, because the gays always cluster together. By virtue of that, they become friends and vacation together.” Even more importantly: “They support each other, whether that’s to hire someone or angel invest in their companies or lead their funding rounds.”

Some of these networks have begun to spill into public view. There is a Substack called Friend Of, written by Jack Randall, who formerly worked in communications at Robinhood, that chronicles gay ascendence into the centers of power. “We run the tech mafia (see Apple, OpenAI),” Randall writes. “We hold top government posts (see the Treasury Secretary). We anchor primetime news and the NYE Ball Drop. Our dating app’s stock outperforms its straight peers. And in the US, gay men are, on average, better educated and wealthier than the general population.”

A new company called Sector aims to formalize this network. Founded by Brian Tran, a former designer in residence at Kleiner Perkins, Sector has a website that features photos of handsome men on beaches and at dimly lit dinners. One member describes it to me as a curated network where introductions unfold between well-heeled gay men with shared interests. “It’s up to you to decide,” the member tells me. “Is this professional, is it platonic, or is it something romantic?” In an interview with Randall, Tran said, “I think we could displace Grindr in the coming years.”

On any given week in San Francisco, Partiful invites float around the community. If there is a “regular Halloween party, the gays will have their own Halloween party, and Sam Altman will be there,” says Jayden Clark, a straight podcaster who hosts a tech culture podcast and was not invited to the gay Halloween party. (Altman attended dressed as Spider-Man, a nod to Andrew Garfield, who played the superhero and has since been cast as Altman in an upcoming film.) I hear of not one but two White Lotus–themed gay tech parties, both equally extravagant. “Girls are not present,” says that same angel investor. “They are just not there.” There is also a “Gay VC Mafia” group chat that is, as one member describes it, “60 percent business” and “40 percent hee hee ha ha” about “classically gay topics.” With a steady churn of tech events aimed at gay men, the social incentives stack up fast. Connections blur—“professional, physical, or sometimes romantic,” as an AI founder puts it. The pull of this bubble is so strong, he continues, that it’s “an uphill battle to socialize with straight people.”

None of this is necessarily unfamiliar in the clubby world of Silicon Valley, where the smart, successful, and wildly rich have always formed in-groups. There’s the so-called OpenAI mafia and the Airbnb mafia, and before those the PayPal mafia—alumni of moonshot companies who bankroll the next wave of startups. So some of what reads as advantage is, on closer inspection, structural and unremarkable. San Francisco combines two things in unusual density: one of the country’s largest gay populations and a tech industry that has reshaped global power. “For sure, gay men are overrepresented and have had an unbelievable run in the Bay Area,” says Mark, another gay entrepreneur who runs an AI startup. “In a city that has the most venture capital in the world, it isn’t surprising that this money is going directly to gay men.” (This perception, for what it’s worth, runs counter to statistics: Between 2000 and 2022, the years for which data is available, only 0.5 percent of startup venture funding went to LGBTQ+ founders.) “It’s not that there is some kind of gay mafia,” Mark continues. “But if I told you who are my friends that I want to invest in, they happen to be gays. Who are the people without kids who can grind away on the weekends? It’s the gays.” (Sources identified in this story by a first name only, like Mark, preferred the use of pseudonyms.)

Imagine this, Mark says: You are a young, nerdy, closeted gay man. You grow up never quite fitting in. Your parents start asking questions. Why don’t you have a girlfriend? You tell them you’re too busy for a relationship. Eventually, you move to San Francisco, a city that, as one person puts it, is like “Disneyland for gay men.” Your world opens up. You meet other people like you—men who are openly out, many for the first time in their lives. These men happen to be working at influential companies. They are building technology that is astonishing. And slowly it dawns on you: Maybe you, too—a person who has spent a lifetime overlooked and underestimated—can build something extraordinary. “Gays feel,” Mark says, “that they have something to prove.”

This is, more or less, the nature of how power and money have moved throughout networks since the dawn of time. And gay networks seem naturally aligned to the dynamics of venture funding, where established wealth meets emerging talent. “One of the key things to realize is that gays are different than straights in many different ways,” says a longtime gay venture capitalist. “Gays are cross-generational.” While straight people tend to spend more time with people their own age, “that is not true with gay men. I can hang out with someone at an event who is 18 years old, and Peter [Thiel] might also be there.”

Just because you are gay and work in tech does not necessarily mean you are part of the so-called gay tech mafia. Much of the queer spectrum is conspicuously absent from events geared toward gay founders. “There are barriers within the community,” says Danny Gray, a leader at Out Professionals, a networking organization for LGBTQ+ businesspeople. “Cis gay men are the biggest gay group within the acronym, and it is much harder for other letters.” Lesbians tend to be sidelined; when I ask the hyperconnected tech journalist Kara Swisher about the gay tech mafia, she says she wasn’t aware there was one. And even if you are a gay man, inclusion is not necessarily guaranteed. “I’ve found it hard to break into this group myself,” one gay investor tells me. “I probably need to lose 20 pounds.”

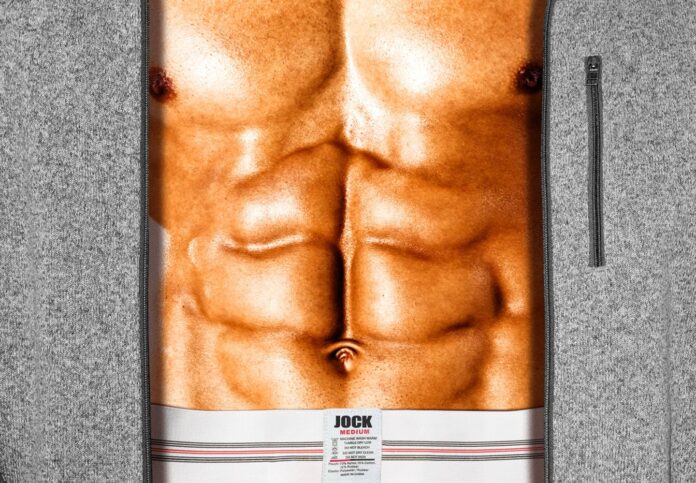

It may be that what outsiders perceive as the gay tech mafia is not gay people working in tech, or even, broadly speaking, gay men, but a small, self-selecting group with shared politics and sensibilities. They are assumed to prize aesthetics and the masculine physique, scorn identity politics, reject DEI in favor of MEI—“merit, excellence, and intelligence”—and lean right-wing, if not MAGA. I’ve heard straight entrepreneurs describe them as “the Greco-Roman gays,” part of “an insular, hypermasculine culture” in which “women are seen as totally redundant and completely unnecessary.” (A woman who once worked for a gay Republican startup founder describes it like this: “You get about the same amount of misogyny, but not the sexual harassment. So that’s nice.”)

Where, then, might these almighty power gays be observed in their natural habitat? This is one of the guiding questions in my research, the answer to which perpetually evades me. When I ask a gay investor if perhaps I can attend one of these parties as a fly-on-the-wall observer, he tells me no, because it would be weird, given that I am—unfortunately for the purposes of this story—a woman. “People will be like, ‘Is that your sister?’” he says. I float an idea past my editor that I attend a party disguised as a man. Perhaps, I suggest, we should discuss the budget for my makeover? While not entirely disinterested in the idea, my editor offers another suggestion, that he—a gay man—come along as a kind of chaperone, “for safety” purposes. Neither of us revisits the idea.

There is one place, though, that is mentioned again and again: Barry’s, the fitness bootcamp, which has become a gay mecca, thanks in part to the high-profile investor Keith Rabois, who has long been one of its most avid devotees, to the point of teaching occasional classes. And one Barry’s in particular keeps coming up: “The Barry’s in the Castro is ranked supreme,” says that same gay angel investor. “It is all guys, all gays, and everyone has abs.” (“From what I’ve learned working here, gay men do love to work out,” confirms a female employee at the Castro Barry’s.)

The fact is, most people seem eager to talk about this, no deceptions on my part necessary. Many of them reply almost immediately to my vague inquiries. Even more surprising is their willingness to talk at length. Calls often run for hours, blending measured observations about life in a masculine-dominated culture with tours through the most salacious industry intrigue of my entire career. There can be an edge to the gossip, though—an implication that one of the most reliable paths to power in Silicon Valley may run through the bedroom. Some men are eager to hop on a call to ask what I may or may not have already heard about them. One gay founder tells me how a rumor has been circulating (a version of which I have, in fact, heard) that he and his husband slept with a gay investor in exchange for a down payment on their home. “Do people really think,” he wonders, “that we can’t afford a condo?”

Many have, at some point or another, been suspected of romantic involvement, even if they’ve never been in the same room together. When I call up Ben Ling, an investor and early Google employee, to ask about long-standing speculation that he might be a good match for Tim Cook—a pairing intriguing enough to be referenced in The Atlantic—he laughs. “People make up these rumors because they have nothing better to do,” he says. “Tim Cook does not know who I am.”

And while it is true that at least some of these men know and see each other socially, these meetups do not reliably lead to romance. A friend of Rabois tells me that Rabois likes to tell a story of the time, years earlier, when he invited Sam Altman as his plus-one to an event. “He said that Sam brought two phones and was texting on both of them the entire time,” the friend says. “Keith says it was the worst date he ever went on.” (Use of the word “date” has, by relevant parties, been disputed.)

For rising figures who have formed genuine friendships with powerful gay industry leaders, success sometimes comes with a penalty: the assumption that it is borrowed, not earned. Brad, a gay industry leader, has long lived with rumors about his friendship with Peter Thiel—rumors that followed him even as his career advanced. “When I started working with Peter so long ago, people would be like, Oh, did you sleep with him? Blah blah blah.” The answer, he says, is no. And yet, “for some reason everyone felt perfectly comfortable asking me about it. Straight people were interested in it generally, but the people who were really fucking fascinated were other gay guys. Guys would be like: What does he have that I don’t have? So then they assume, Well, Peter must have thought you were cute.” (Thiel did not respond to requests for comment.)

Still, it’s naive to insist that intimacy with power is without its advantages. When Altman’s former boyfriend, early Stripe employee Lachy Groom, raised a $250 million solo venture fund while still in his twenties, some observers read the achievement less as an anomaly of talent, I’m told, than as an artifact of access. This interpretation, according to a gay investor close to both Groom and Altman, is not entirely fair: “When Lachy and Sam were dating, Sam was kind of famous, but not nearly as famous as he is now, and Lachy was a person in his own right,” the investor says. “I did give a reference to [an investor in Groom’s fund] saying, ‘Yes, he’s unproven as an investor, yes, he’s young. But he is in the network, and he is Sam’s ex-boyfriend.’ But Lachy didn’t date Sam to get these things.” (Groom declined to comment on the record, as did a representative for Altman.)

Meanwhile, when straight men attempt to tap into the gay network, the gay investors chat amongst themselves. Mark, who hosts dinner parties and events for the gay tech community in San Francisco, says that he noticed one man constantly RSVPing to his events. “We don’t have a purity test,” he says, “but someone said that guy is definitely not gay, he just goes to the gay man events because he wants deal flow.” It isn’t like straight men are excluded per se, but they are not exactly a welcome addition to the world of gay capital. The joke, if a straight founder does show up, is: Just don’t tell anyone you’re straight.

“I have seen straight men do untoward things,” says a gay investor. “There is a straight guy who is not important enough to be named who would pitch all the gay investors, and in one meeting at the VC partnership he was talking to a gay general partner who I know. And in the meeting, this guy put his hand on the GP’s leg under the table. It is so inappropriate. It became a running joke, like, not this guy again.”

One person in particular has helped fuel the notion that being gay can benefit one’s career: Delian Asparouhov, the mischievous, 31-year-old cofounder of Varda Space Industries, who was once hired as Rabois’ chief of staff. Rabois, who helped Thiel start PayPal and was later a partner at Thiel’s venture firm, Founders Fund, was a subject of corporate scrutiny years earlier. While at Square, Rabois was accused of sexual harassment by a male colleague, an episode that ultimately ended with Rabois’ departure from the company. (After an internal investigation, the company backed Rabois.)

In 2018, about 100 people attended Rabois’ wedding to Jacob Helberg, a former adviser at Palantir who currently serves as the US undersecretary of state for economic growth. The wedding was a multiday affair with a guest list that included many of the most important people in tech and culminated in a beachside wedding ceremony officiated by Sam Altman. (Rabois’ bad “date” with Altman resulted, apparently, in close friendship.)

During the wedding, Asparouhov gave a toast, which was later recalled by Fred, a longtime gay tech leader who was in attendance. “Delian said something like, ‘I’m the intern that Keith hired, and I would wear short shorts and tank tops at Square.’” Fred says he was sitting at a table with two famous tech executives. “We just raised our eyebrows,” Fred continues. “It was so embarrassing that Delian would say that at someone’s wedding. I mean, here was Keith getting married to Jacob.” (Other wedding attendees claim not to remember the contents of the speech but say it sounds like Asparouhov.)

Rumors of Asparouhov and Rabois’ dating lives have long traveled in industry circles, thanks in part to Asparouhov, who has fanned the flames online. (“Delian is like Gretchen Wieners,” explains Fred.) In 2022, a popular anonymous tech insider X account, Roon, tweeted that it was “crazy how venture capitalists have reinvented the Roman system of pederasty.” Asparouhov responded to the tweet almost immediately: “It only took a little gay and now I get to work on space factories,” he wrote. “Pretty reasonable trade.” Asparouhov, who is married to a woman, now says the tweet was “obviously a joke.”

But as Fred recounted, Asparouhov was known for wearing neon tank tops, short shorts, and mismatched shoes when he joined Square in 2012. “He would jump a lot—it was very odd,” says someone who worked at the company at that time. Others have similar recollections. OpenStore, the Miami-based company Rabois cofounded in 2021, which mostly shut down last year, seemed to be, according to John, who says he visited its offices, “almost like a harem, filled with jacked white men, all of them handsome and good-looking, straight and gay. People were wearing kind of inappropriate clothing: really short shorts and tight shirts even though the AC was blasting.” Rabois, when I ask him for a comment, denies this categorically. “Attire was quite standard for Florida,” he says. “And I doubt more than two of the 100-plus employees could be reasonably described as ‘jacked.’”

Rabois has been known to take extravagant vacations—helicopter trips to Icelandic volcanoes, white-water rafting in Costa Rica. Exclusion can stir serious envy, as it did with one young gay tech consultant I speak with who says he has begun a kind of “micro-journalism” project to track the appearances of a couple of guys on Rabois’ Instagram. These are “low-level” workers, he says, who nonetheless are “always posting photos in St. Barts.” “Here I am doomscrolling on the A train, and I’m like, ‘How are these guys on a private jet?’”

But how far back do these rumors really go? Has Silicon Valley always been semi-secretly, kinda-sorta gay? More than once, I’m told to connect with Joel, a gay man who works in tech and who spent a lot of time among the older in-group of powerful gay men in Silicon Valley, more than a decade ago. “So,” I say when he answers my call, “are you a member of the gay tech mafia?” He laughs. “Maybe someone thinks I’m in it, which is why you’re calling me.”

When I ask Joel to explain how the gay tech mafia works, he tells me that it’s similar to people who “went to the same college or came from a similar background or a similar town.” And it indeed started, he says, with people like Rabois and Thiel, who, after they rose to power, “brought a lot of people along. Keith hired gays at Square, and Peter hired Mike [Solana] at Founders Fund. Then there was a cohort of Google gays that Marissa Mayer ran in 2010. And there is Sam, who is friends with Keith, and Sam was running in parallel, assembling other gays around him.”

Joel tells me about the parties at the time—the exact specifics of which remain off the record. But they were, in summary, what you might expect. “There was lots of drinking that would turn into weird situations. Random people hooking up. Generally, there was a sexual tone.” But this was years ago. These types of parties, at least from what I’ve heard, have either disappeared or moved entirely underground. (“Once you get to the end of your reporting, you will find that the real story is much less explosive,” says Mark. “Like all these wild orgies: If you do find out where they are, please tell me, because I’d like to go.”)

I tell Joel that I’ve heard from some young men in the tech industry who feel pressured to sleep around to get ahead. Was that true in his experience? “Mmmmm,” he says, and pauses. Then he bursts out laughing. “I mean, in all of this, there are weird gray areas. It can be very sexual. It is not all professional. A lot of people have dated or slept with each other.” He had experienced a kind of coercion firsthand. “I definitely felt pressured to do—not overtly illegal things. But they walked the line.” Joel is older now, and while he can see how someone might describe this as an abuse of power, he resists the framing. The exchange of sex and status may not be the reason these men rose so quickly, but it can be a factor—if only because sex, as he puts it, “makes people become closer rapidly.”

As Silicon Valley has matured into the power center of the world, it has grown sharply cutthroat. Leverage is scarce, and ambition is often laced with a kind of ruthless opportunism. In gay circles, some feel the Valley resembles the old Hollywood casting couch. Many of the critics are rising gay entrepreneurs and investors themselves, for whom parts of the gay community seem steeped in the attitudes and values of the 1970s and ’80s. “There’s this feeling,” one observes, “that because there were years of historical oppressions only recently recognized, certain people think, ‘I can do this, or I deserve this, because no one will cancel me for it.’”

This is a community that, as one young gay investor describes it, is “power-hungry, network-driven, and, at times, very horny.” The arrangement, he suggests, is tacitly understood by everyone involved: “Both sides know they are in the game and want something from each other. Which is fine, I guess, if you’re into that.” This is not, in his telling, the whole of the gay tech scene, most of which is a “lovely, amazing community that supports its people and their career progress.” But alongside that exists a sexual undercurrent—one that, he insists, is impossible to deny and especially pronounced in AI circles. “It’s like a gay nepo thing,” he says. “While it’s not explicitly for sexual favors, there is an element at work in the background. Like, you’re young and you’re hot and I’m down to hook up.”

One gay man, Dean, describes moving through a professional world in which sexual suggestion flowed freely. Early on, it came from limited partners curious about his prospective fund; after he raised the fund, it came from founders seeking capital. In one instance, a potential limited partner proposed a meeting at his home. “He was like, ‘We don’t need to wear clothes, we can just sit around and talk about your fund in my hot tub.’” Dean frames these encounters as an irritation—ambient, expected, and largely inconsequential. “Sex is devalued in gay male culture,” he says. “Often, it’s just another piece of currency.”

After Dean raised his fund, he was occasionally approached by young men, “founders looking for money who indicated they were open to whatever it takes to raise it.” At events geared toward LGBT founders, young men would ask to grab drinks one on one. Sometimes, they’d send nudes on Instagram. “Like ‘Hey …’ with a winky face. And ‘Do you like that?’ And I’d be like, ‘No, that’s actually inappropriate,’” he says. It’s not confined to Silicon Valley, he adds. Having left tech for a different industry, Dean has come to see the entanglement of sex, power, and ambition as a recurring feature of certain pockets of gay professional life.

Another man who works in the queer tech space puts it this way: “There is an aspect of being queer and in business and in life and having relationships that can be frankly sexual and not sexual at the same time. You can turn off and do business with someone you were hooking up with yesterday.” Plus, he continues, there is the inescapable fact that much of gay male culture tends to be sexually charged. “Straight guys have the golf course. Gay guys have the orgy,” he says. “It doesn’t mean it’s problematic. It’s consensual, but it is a way we bond and connect.”

Of the 31 gay men I spoke to for this story, nine tell me they experienced unwanted advances from other gay men in the industry. Some of these advances were mild but annoying: repeated invitations to soak in hot tubs or explore wine cellars. Others involved unwanted touches. One person, an up-and-coming gay investor, tells me that he believes that turning down a sexual advance from a senior colleague cost him a job. Multiple sources speak of “sex pests” who send unsolicited dick pics and make overt come-ons.

“What demoralizes me in the conversations around the gays in tech in San Francisco is that none of this is entirely a secret,” says one gay investor who experienced an unwanted sexual advance. “People are aware this is an issue.” Another gay man who works in tech adds: “There is an element to this story that is a cautionary tale. You take a brilliant entrepreneur who has a great idea trying to make it in the world of venture capital. And then they have to put up with someone sending them dick pics and asking for an investment meeting. It shouldn’t be normalized. And right now, everything is so gray. Like, it’s our little thing, our little world. But it has a massive impact.”

Again and again, gay men working in tech ask me: Why has this story never been written? The question somewhat answers itself. Unfair stereotypes about gay men persist, and why else would sources insist on pseudonyms? I am warned, more than once, to be careful, that figures in Silicon Valley are “vindictive.” Even as many consider this culture of sexual pressure a feature of Silicon Valley life, it is, as someone else tells me, “a true minefield” to write about.

| Got a Tip? |

|---|

| If you have stories from inside the so-called gay tech mafia, you can send Zoë Bernard a confidential tip on Signal @zoebernard.26. |

Gerald knows the feeling. He’s a young gay man in San Francisco, described by acquaintances as a “quirky individual” and a “social puppeteer.” Over a call, Gerald lays out the reasons he has hesitated to talk about his time in tech. “This is a complex subject,” he says, “and I don’t think readers can draw the distinction between some bad men being gay and all gay men being bad. It can be a slippery slope into homophobia.”

He won’t give his story to me. Not yet. But he does tell me he suspects that other stories, in the coming months, will surface. “People have a difficult time articulating power with nuance,” he says. “This is not just one story. There will be many.” From what he’s told me so far, and from everything else I’ve heard—the heartfelt, late-night confessions over the phone; the insights shared quietly and kept off the record; the admissions of dozens of funny, brilliant, young gay men competing for, yes, power and money and recognition, but also for love, romance, and a place to belong in the heart of San Francisco—I believe him.

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: wired.com