Have you run across the term “down fill power” while shopping for sleeping bags, puffer jackets, or a duvet? These numbers range from 450 to 900, and sometimes above. Generally—but not always—the higher that number, the better the warmth-to-weight ratio. But what does fill power actually measure?

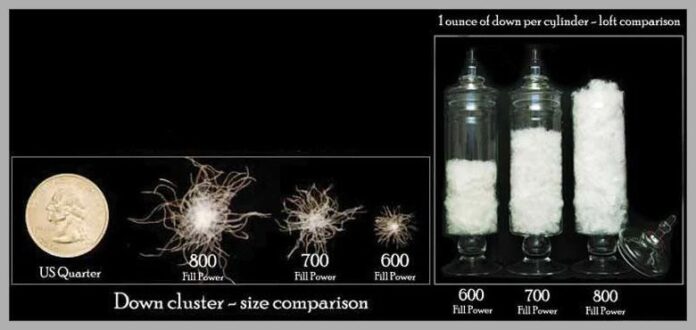

To measure fill power, companies perform a lab test to measure the fluffiness of down. The technical test is how many cubic inches of loft come from one ounce of down. A container is filled with one ounce of down insulation, then a weight is placed on top. After one minute of being compressed by the weight, the volume of down under the weight is measured. The important thing to keep in mind is that fill power is a measure of the quality of the down, not the quantity. Higher fill power means larger down clusters, and larger down clusters fluff up more than smaller down clusters. The graphic below illustrates the difference in loft between various fill powers.

Outdoor gear generally ranges from 500 fill power at the low end to over 900 fill power for high-end ultralight jackets and sleeping bags intended for cold-weather backcountry adventures. The loftiness (that is, the higher fill power) also means that the parka or sleeping bag will compress down much smaller, making them more packable for travel or backpacking.

Updated February 2026: We’ve added a new section on caring for down and some notes on Outdoor Vital’s Zero Stitch fabric.

What Does Down Fill Power Tell You?

The higher the fill power, the greater the loft. Down puffer jackets and sleeping bags keep you warm by trapping the warmth coming off your body, retaining it in air pockets between the down. A higher down fill power means the down has more loft, which means there are more air pockets, which means that more heat is retained. If everything else is equal, that means that a higher fill power garment will be warmer than one with a lower fill power.

Unfortunately, everything else is never equal. Fill power alone is not enough information to know how warm something will be. There is no direct correspondence between fill power and how warm a product will keep you, because there are many other factors to consider, like how much of that fill is in the product, how well it can expand within the baffles or down chambers, how well does the fabric stop the wind, and so on.

To know how warm a down jacket, sleeping bag, or comforter will be, you need to know at least one other number: the fill weight.

What Is Down Fill Weight?

Down fill weight is a simple number. It’s the amount of down in the product, usually measured in ounces or grams. Using down fill weight and down fill power together can give you way to compare two items. For example, the relative ability of a puffer jacket to retain heat can be estimated by multiplying the fill power by the fill weight. This means that a 900 fill power jacket with 2 ounces of fill weight will be able to trap about the same amount of heat as a 600 fill power jacket with 3 ounces of fill weight. The big difference between them, and the reason they are priced differently, is the weight of each and the packed size.

In jackets, the weight difference isn’t huge. This is why some of our favorite puffer jackets are 600 fill power. When it comes to sleeping bags, though, things are different. Since there is a lot more down in a sleeping bag, the weight difference between equivalent amounts of fill power is more significant. Unless your budget is unlimited, you’ll want to pay attention to the warmth-to-weight ratio. How much warmth do you need, and how much weight do you mind carrying?

The one downside to down fill weight is that some manufacturers don’t list this. It sounds great to say your puffer jacket as 900 fill power down, but when you have to list that it only has 2 ounces of it, it sounds less impressive. Less reputable companies often don’t advertise the fill weight. We list fill weight of all the jackets we test.

Other Factors to Consider

While down fill power and down fill weight together give us a way to compare items, there are other things to consider to get an idea of overall warmth. The third major factor is the baffles, the compartments that are built into the product. If you just sewed up a single piece of nylon as a shell and shoved some down inside, gravity and movement would push it all down near the hem in a matter of minutes. To avoid this, garment makers add baffles to keep the down in place. Baffle type and shape play a big part in how warm your jacket, sleeping bag, or comforter ends up being.

The cheapest and most common form of baffle is a sewn-through baffle. As the name suggests, the chambers are stitched in place, with thread passing through the outer shell to the lining fabric, trapping the down between. This is the lightest-weight baffle, but the down side (sorry) is that the large chambers mean down can settle more, leaving potential cold spots.

The box baffle technique still stitches through but makes little boxes, which do a better job of keeping the down in place. Box baffles are slightly warmer. The third major method of baffles is what’s called welded baffles (also sometimes heat-seamed). This eliminates the seam, which makes a jacket more wind resistant (since there’s no stitching holes for the air to pass through).

Recently I tested a fourth method of constructing baffles that the company Outdoor Vitals refers to as Zero Stitch fabric. As the name suggests, the technique uses no stitches. There are still baffles to keep the down in place, but instead of punching thousands of little holes as you would with stitching, the baffles and other seams are woven into the fabric. Where the conventional method has an inner and outer fabric that is then either stitched (or bonded/welded), the Zero Stitch fabric is two pieces that are woven together. It’s hard to visualize how this works, but Outdoor Vitals has a video to explain.

The Zero Stitch fabric helps stop wind (it also stops water and, particularly, dust, which is one of the biggest reasons down breaks down over time and loses loft), and that means that against jackets with the same fill power and same fill amount, it might still be warmer on a windy day.

Another things to consider is how much room there is for the down to expand. If you have a sleeping bag with 1,000 fill power but not enough room for that down to fully expand, then it won’t be as warm as it could be. This is the toughest thing to measure. Few manufacturers list stats like loft height or garment thickness. But if you’re looking at two sleeping bags with equal fill power and equal fill weight, but one is noticeably fluffier than the other, chances are the fluffier one will be warmer.

Different Kinds of Down

Most down is goose down, but manufacturers have started using duck down to keep prices lower. In my experience testing puffer jackets and sleeping bags, there isn’t a huge difference between the two, but right now most of the highest-quality down products on the market use goose down or Muscovy duck down.

Another thing to look for is whether the down comes from sources approved by the Responsible Down Standard. You’ll often see that abbreviated “RDS approved.” The RDS is a voluntary standard that is trying to get the down industry to treat ducks and geese more humanely. It’s not perfect, but if you’re concerned about the ethics of down, looking for the RDS seal of approval is good place to start.

Caring for Down

The warmth of your down lies in the loft. In general, compressing down means losing loft over time. Never store your down compressed for long periods of time. I keep my jackets in large bin with a tight fitting lid, and I keep my sleeping bags in the provided storage bag, not in a compression sack. Even on the trail I don’t stuff down my jackets, I usually just shove them loosely at the top of my pack. This way they’re not overly compressed when I get to camp and want to put them on.

Most manufacturers suggest washing your down. (Notably, the North Face does not. It suggests taking your down to a professional cleaner.) However, each manufacturer has different instructions on how to do that. Your best bet is to look up what’s suggested for your model either online or on the tag if you still have it.

Because I test things, I don’t always follow the instructions, so I can see what happens if you don’t. But down is the one place though where I don’t mess around much. I use a dedicated down detergent (I’ve used Granger’s Down Wash with good results) and a front-loading machine. (If you’re washing a sleeping bag, make a trip to the laundromat so you can use a big front-loader.)

To dry, use the lowest possible setting. Get some tennis balls or wool balls, which will help speed things up, but no matter what you do, it’s going to take a long time, a very long time, especially for something like a 0-degree sleeping bag to dry. Be patient and check on it every 30 minutes for so. Also, when you think it’s dry, it’s not really. To combat this, even when I think it’s totally dry, I then lay out the garment for a couple of days to make sure it’s 100 percent dry before I put it back into storage.

The big question is how often you should wash your down. Not that often. I avoid washing until I feel like there’s a noticeable loss of loft and warmth.

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: wired.com

.jpg)

.jpg)