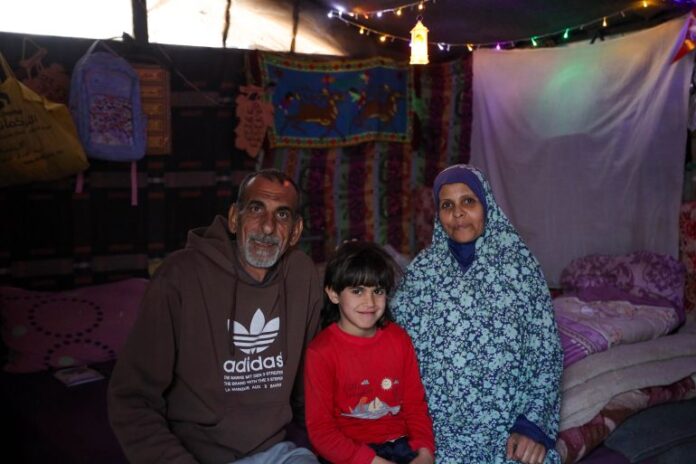

Central Gaza Strip – At the Bureij refugee area in central Gaza, Maisoon al-Barbarawi welcomes the Islamic holy month of Ramadan in her tent.

Simple decorations hang from its worn ceiling, alongside colourful drawings on the fabric walls, prepared by camp residents to mark the arrival of the blessed month.

Recommended Stories

list of 3 itemsend of list

“We brought you decorations and a small lantern,” Maisoon tells her nine-year-old son, Hasan, smiling with an exhaustion tinged with joy at her ability to buy him a Ramadan lantern.

“My means are limited, but what matters is that the children feel happy,” Maisoon tells Al Jazeera, expressing cautious optimism about the month’s arrival.

“I wanted these decorations to be a way out of the atmosphere of grief and sadness that has accompanied us over the past two years during the war.”

Maisoon, known to everyone as Umm Mohammed, is 52 years old and a mother of two children.

“My older son is 15, and the younger is nine years. They are the most precious things I have.”

“Every day they are safe is a day worth gratitude and joy,” she says with pride mixed with fear, referring to the terror that has accompanied her throughout the war at the thought of losing them.

Like other Palestinians in Gaza, what distinguishes this Ramadan is the relative calm that has come with the current ceasefire, compared with the previous two years, when Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza, which has killed more than 70,000 Palestinians, was at its peak.

“The situation is not completely calm,” Maisoon explains. Everyone knows the war hasn’t truly stopped; shelling still happens from time to time. But compared to the height of the war, things are less intense.”

Advertisement

Maisoon participates in camp administration activities, helping prepare bread and arrange dates and water for distribution, minutes before the call to prayer on the first day of Ramadan.

“This is the third Ramadan we’ve spent in displacement. We lost our homes, our families, and many loved ones.”

“But here in the camp, we have neighbours and friends who share the same pain and suffering, and we all want to support one another socially.”

Maisoon lost her home in southeastern Gaza at the beginning of the war and was forced to flee with her husband, Hassouna, and their children, moving between camps before eventually settling in Bureij under what she describes as “very bad conditions”.

“We are trying to create life and joy out of nothing. Ramadan and Eid come and go, but our situation remains the same,” she says after a brief pause.

‘Wounded from within’

Maisoon’s words fluctuate between optimism and fear, but she insists that Ramadan is “a blessing”, despite everything around her.

On the first day of Ramadan, she had not yet decided what she would cook for her family, as her limited means would only allow for a modest meal.

But she had already prepared her prayers and wishes before breaking her fast.

“I will pray that the war never returns. That is my daily prayer: that things calm down completely and that the army withdraw from our land,” she says, pointing to bullet holes in her tent caused by gunfire from an Israeli quadcopter drone days earlier.

Fear of the war’s return during Ramadan is not unique to Maisoon, but is shared by many across the Gaza Strip, who worry about a renewed escalation, similar to last year when fighting resumed on March 19, 2025, coinciding with the second week of Ramadan.

That renewed war was accompanied by the closure of crossings and a ban on food aid entering the enclave, triggering a severe food crisis and humanitarian famine that lasted until last September.

“People these days keep talking about stocking up. They tell us: store flour, store food… the war is coming back,” Maisoun says anxiously.

“Last Ramadan was famine and war at the same time. I spent all my money during the previous famine.”

“My little son used to pray for death because he craved food. Can you imagine?”

Bitter memories

Gaza enters this year’s Ramadan under a “ceasefire” that began on October 10, 2025.

Advertisement

That truce remains fragile, but reports from the World Food Programme (WFP) and the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) indicate a relative improvement in the availability of certain food items, compared with periods of severe escalation and closures.

Commercial activity has partially resumed, and aid has entered at a steadier pace, though the flow remains inconsistent and subject to restrictions and logistical obstacles.

Despite a broader range of goods appearing in markets, prices remain high, and purchasing power is severely weakened, with large segments of the population still reliant on humanitarian assistance to meet basic needs.

Many Palestinians in Gaza continue to rely on aid organisations to eat.

Hanan al-Attar is one of them. She received a food parcel from a relief organisation on the first day of Ramadan.

Opening the package with a broad smile, she celebrates its contents while her grandchildren gather around her.

“This is fava beans, halva, dates, tahini, oil, lentils, beans, spreadable cheese, mortadella, mashallah, an excellent parcel,” Hanan tells her daughter standing nearby.

“This will be perfect for tomorrow’s suhoor,” she says, referring to the predawn meal before Muslims begin fasting for the day.

Hanan, 55, is a mother of eight who fled to Deir el-Balah a year ago from Beit Lahiya in northern Gaza, one of the hardest-hit places by Israel during the war.

She tells Al Jazeera that she will have to depend on whatever aid arrives to sustain her during Ramadan, due to her difficult economic situation.

“Today, thank God, we received assistance. This will ease my worry about what we will break our fast with,” says Hanan, who shares a tent with 15 family members, including children and grandchildren.

Smiling, she admits she secretly set aside a small amount of money to prepare a tray of potatoes with minced meat and rice for the first iftar.

“I saved a small amount to buy a kilo of meat tomorrow. Fasting requires protein,” she says in a low voice, noting that preparing a meal now depends entirely on what is available that same day, as storage conditions are nearly nonexistent.

“As you can see, there is no electricity, no infrastructure, no refrigerators to store vegetables or meat if we buy them.”

“We purchase what we need day by day so the food does not spoil.”

Yet the other side of Ramadan for Hanan is measured not by preparation but by those absent from the table.

Tears fill her eyes as she mentions her two sons in their late twenties who were killed in a strike last year, one leaving behind a daughter not yet two years old.

“This is the first Ramadan after the martyrdom of my sons Abdullah and Mohammed,” she says through tears.

“You feel the emptiness. It’s hard. When the family gathers and members are missing, you feel deep pain.”

Cooking in the tent: Fire, wind, and plastic

Still, Hanan’s sorrow is briefly interrupted by the practicalities of preparing the cooking space.

Advertisement

“Unfortunately, Ramadan hasn’t changed our reality. We’ve been cooking over open fire for two years. The wind blows out the flame, and my son tries to shield it with plastic.”

She relies on firewood due to prolonged shortages of cooking gas.

“I managed to fill an eight-kilo gas cylinder two months ago and refused to use it until Ramadan,” she says, pulling out the hidden cylinder.

“Gas is like treasure for us. I planned to save it for suhoor or something quick. It would be difficult to light a fire at dawn.”

“In the end, everything passes. What matters is that we remain together in health and safety, and that we do not live through famine or war again,” she adds, her voice shifting to prayers for peace.

The memory of famine further deepens her anxiety.

She repeats the word “difficult” as she recalls the months when prices soared and food disappeared after last Ramadan.

She describes grinding lentils to replace flour and mixing them with pasta or rice to feed as many family members as possible.

To make the bread stretch, she cut it into smaller portions.

“I make it smaller, so it’s enough for everyone.”

And yet, her final wish, repeated like a prayer, echoes what many in Gaza seek this Ramadan: nothing more than “goodness and peace”, and a return home from displacement.

“May this Ramadan be one of goodness and peace for everyone… and may we return to our homes and our land.”

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: aljazeera.com