If you are well-versed in the Book of Tiger, certain figures from his (nearly) 50 years on this earth are so familiar to you no surname or ID is required. Tida and Earl, of course. Stevie and Steiny; Butch, Hank. (For those late to the party: caddie, agent, swing coach, swing coach.) His kids, Sam and Charlie. I was on the scene for Tiger’s second U.S. Amateur title and 14 of his 15 wins in Grand Slam events. If “Jeopardy!” ever had a category called Tiger Times, I like my chances. So you can imagine my shock when I sat in a cart at the Ryder Cup last month and interviewed a man for two hours who has worked with (and on) Tiger Woods for 27 years and I had never heard of him in my life!

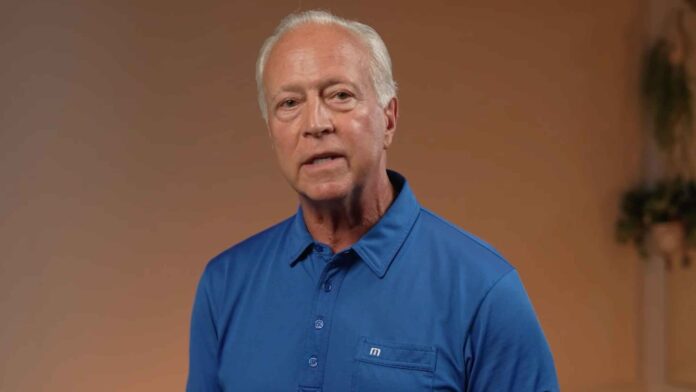

The man’s name was (and is) Dr. Tom LaFountain. He’s a chiropractor and the director of the PGA Tour’s chiropractic services. Our matchmaker was Johnny Wood, the caddie-turned-broadcaster who served as the U.S. team manager for the Ryder Cup at Bethpage, where LaFountain, who is 69 and white-haired, was in charge of all manual sports medicine for the U.S. team. “He’s probably worked on every great player of the past 30 years or so,” Johnny told me. By which he meant Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus as senior golfers; Tiger Woods, Phil Mickelson, Jim Furyk and Davis Love in their long primes; Rory McIlroy, Keegan Bradley and scores of other Ryder Cup players through the years.

Tiger Woods got on the PGA Tour in 1996, by way of sponsor exemptions and his out-of-the-box superior play. Tom LaFountain, soft-spoken and country-strong (upstate New York), got on Tour the next year, by way of his work with all manner of athletes, most especially the legendary Olympic speedskaters Bonnie Blair and Dan Jansen. Manual sports medicine was not a phrase in circulation then, and isn’t exactly coffee-shop ready now. But it is very much a real thing. When LaFountain and the dozens of trainers and chiropractors under him (many of them coming to Tour events on a freelance basis) get to know their patients through their hands. No gloves, ever.

Their exams go from toes to neck, by way of hand. LaFountain can encounter left-ankle tightness and ask, “Are you feeling something in the first foot of the backswing?” How’d you know? Chances are good that whatever the issue is, there’s an app for that. LaFountain and his people will do their thing, and leave the player with homework, too. The player wants the work because he wants to shoot lower scores and be pain-free doing it.

More than once, a touring pro has said to LaFountain, “You’ve got good hands.” It’s a favorite compliment. He finds issues with his hands and he finds fixes problems with his hands. Shaking hands with him is like shaking hands with Babe Ruth’s baseball glove. LaFountain, in the 1960s, was a Little League legend, for his homerun prowess, in greater Utica, N.Y., where he still lives half the year. He spends the other half at the Bear’s Club, a high-end housing development in South Florida with a Jack Nicklaus golf course. Nicklaus pronounces the chiropractors last name in the French way, La-fon-taine. LaFountain pronounces it the Utica way, as in water fountain.

When LaFountain got on Tour, players were still drinking Cokes at the turn in the name of back-nine energy boosts. It was a different day. “When I got out here, there was a fitness trailer with a Universal Gym in it,” LaFountain said. A Universal Gym is that gleaming chrome weight-lifting contraption with various cables that is the centerpiece of every high school football-and-wrestling training room. “Now we’re getting to where we will have three trailers at tournaments, one for therapy, one for fitness, one for recovery.”

courtesy tom lafountain

The original trailer was a trailer, about what you’d see at a campsite. Now the trailers are 53-feet long and eight-feet wide when they’re on the road (racking up tens of thousands of miles a year, driven by professional drivers out of North Carolina). Once these monster trucks are at tournament sites, they expand like an accordion and triple in width. The Tour spends millions on this whole operation, and gets that money back and then some by way of sponsorship. When Woods turned pro, you associated the PGA Tour with Buick and other GM cars. Now you’re more like to associate it with the Mayo Clinic, official medical source for the PGA Tour. As LaFountain sees it, it is impossible to overstate the influence Woods has had in the transformation of the Tour player into an athlete in year-‘round training.

There’s only going to be more of that. As Tour fields become smaller, and professional golf finds itself awash in money and outside investors, the approach to player health is undergoing a radical change. The day of the golfer having his own health-and-wellness entourage at every tournament is all but over. “It’s interesting, because these players are individual contractors, but our approach now is more like what you see on an NFL team.” When a field has only 70 or 80 players in it, it’s in the PGA Tour’s interest to keep everybody healthy and performing at their highest level. Some will see this as evolution, an adaptation (to use a favorite phrase of corporate America) of “best practices.” Others as another knife in the former cowboy spirit of the pro golfer. Regardless, it’s where the game is, bending in the direction of science over art.

At the Ryder Cup, there was a trainer just for the caddies. At every Tour event, there’s a Tour-sanctioned nutritionist. You want fuel (aka food) advice, the Tour has an expert on hand with answers. And the actual food to go with it.

“Tiger nailed that, years ago — he was ahead of everybody,” LaFountain said. He described Tiger’s early-career Presidents Cup and Ryder Cup team rooms. LaFountain would see players going for a second dessert while Woods was eating grilled chicken and a boiled potato and calling it a night. Everybody saw it. Many changed their ways. Now diet is a way of Tour life. Exercise is a way of Your life. Deep-tissue massage, the same. Chiropractic adjustments, the same. Three-minute plunges in 50-degree water, the same. (“You do hear some f-bombs,” LaFountain said.) Compression therapy boots. Zero-gravity chairs. Stem-cell injections. Along the way, a sea-change in dialogue.

Player: Do I have to come in even if I don’t hurt?

Physio: Yes.

Player: Am I on a ball count?

Physio: Always.

Tiger Woods’s Ryder Cup absence begs question: When, if ever, will he return?

Player: Am I heading toward surgery?

Physio: Not if I can help it.

This month, Tiger Woods underwent back surgery for the seventh time. At the end of the year, he turns 50, which means that 2026 would be the first year where he is eligible for the Senior PGA Championship (at Concession Golf Club next year, the week after the Masters), the U.S. Senior Open (at Scioto Country Club in late June) and the Senior British Open (at Gleneagles in late July). Nobody is really talking about Tiger Woods the golfer these days. Well, not nobody. Tom LaFountain is.

“Tiger is so competitive, he has so much drive, he is willing to work so hard, you can be sure he’s going to do everything he possibly can to get himself ready for those events,” LaFountain said. “He is someone who is always looking for a new challenge.”

In early March of 2019, Tiger Woods was deeply focused on the upcoming Masters. He told LaFountain, “You’ve got 33 days here.” Thirty-three days to help Woods get his body exactly where it needed to be as he tried to win his fifth Masters. As everybody knows, Woods did. Afterward, Woods said, “Tom, thanks for helping make this happen.”

Tiger Woods has good hands. We all know that. Evidently, Tom LaFountain does, too. Who knew?

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael.Bamberger@Golf.com

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: golf.com