TOKYO, Feb 10 (News On Japan) –

The death penalty and life imprisonment, often described as shrouded in secrecy when it comes to the details of executions, continue to provoke debate in Japan, where roughly 1,700 inmates are serving life sentences and many live with the knowledge that they were once candidates for execution.

[embedded content]

A collection of tanka poems recounts scenes witnessed by an execution official who attended hangings, describing the tense moments before the end, the condemned person being led away calmly by a chaplain, sometimes singing hymns, offered tea and cigarettes, and speaking quietly as if acknowledging the moment. When the floor dropped, the condemned reportedly expressed thanks to those present, leaving a lasting impression on the official, who continues to write poems in memory of those executed.

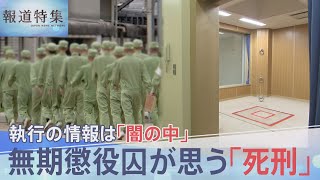

In Tokyo, a massive concrete structure across the Arakawa River houses the Tokyo Detention House, where executions are carried out in a basement chamber known only to a limited number of staff. Officials receive notice from the Justice Ministry a week before an execution and conduct rehearsals using weighted mannequins. The condemned is informed only on the morning of the execution and escorted without delay to the chamber, where some reportedly struggle to walk due to fear.

The warden offers final words, and after a brief religious ceremony, the prisoner is moved to the execution room. Bound at the feet and neck, the prisoner stands on a trapdoor. Three buttons control the mechanism, and it is unclear which officer’s press triggers the drop. Staff members with pregnant family members or serious personal circumstances are excluded from the role. The body falls about four meters and stops midair. After about 15 minutes, a doctor confirms death.

Executions do not always proceed smoothly. In some cases, all three officers have hesitated to press the buttons, or mechanical issues have delayed the process. One prisoner reportedly lashed out after waiting nearly two decades for execution. Father Javier Garralda, who spent 28 years accompanying condemned inmates in their final moments, said executions do not resolve grief. While acknowledging victims’ families’ pain, he argued that killing the offender does not bring peace and ultimately amounts to revenge.

Executions are announced by the justice minister at press conferences, but details are rarely disclosed. One former minister, who attended an execution for the first time in office, described being stunned by the silence and gravity of the process, calling it a deeply cruel act even while carrying out official duties. He had previously opposed capital punishment but said he ultimately could do nothing to halt the system.

Until the late 1990s, executed prisoners’ bodies were often donated to medical schools for anatomical study, with students learning from them for months before cremation. Internal Justice Ministry documents detail the health and legal status of death-row inmates, but the criteria for deciding the order of executions remain unclear, even to the minister.

Some prisoners have filed lawsuits arguing that same-day notification of execution is cruel. Lawyers representing them say the secrecy surrounding executions prevents public debate. They call for greater disclosure to allow society to examine whether the system should continue.

At Okayama Prison, about half of the 450 inmates are serving life sentences for serious crimes, including murder. Nationwide, the average time served by lifers exceeds 38 years. Many once faced the possibility of execution. Some say that being told they would live rather than die awakened a desire to keep going, even while acknowledging the severity of their crimes.

Daily life is regimented, with early wake-ups, exercise, and limited recreation. Annual events like a sports day provide rare moments of excitement. Some inmates say they oppose the death penalty, arguing that offenders should be given a chance to atone through a lifetime of effort. Others admit feeling grateful simply to be alive, even without hope of release.

Aging is a growing issue among lifers. Some have spent decades in prison and have no family left to receive them if released. Rehabilitation facilities for parolees provide temporary housing and support, but many die within a few years of release. Some victims’ families argue that life imprisonment without parole may be harsher than execution, forcing offenders to live with their actions for decades.

One bereaved family member whose brother was murdered for insurance money initially demanded the death penalty but later concluded that execution would not bring relief. He now advocates for a system that ensures offenders remain imprisoned for life, arguing that true accountability requires enduring responsibility rather than a swift end.

As debates continue, executions in Japan proceed quietly, with limited public information. Surveys show about 80 percent of the public supports capital punishment, though critics say opinions are formed without full knowledge of how the system operates. Calls for greater transparency have grown, with some arguing that national discussion requires more openness about what happens behind prison walls.

Source: TBS

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: newsonjapan.com