In an exclusive interview with the director of the National Museum of Iran, we explore the remarkable “Silk Legacy” exhibition currently underway in Tehran. The show offers an unprecedented look at the deep and enduring cultural ties between Iran and China, tracing a connection that stretches back over four millennia.

On Tuesday evening, speaking from his office to the Tehran Times, director Jebrael Nokandeh highlighted some of the exhibition’s most significant pieces, shared the historical context behind them, and discussed what this centuries-old relationship means for modern cultural dialogue between Iran and China.

Featuring carefully selected artifacts, Silk Legacy highlights not only the famed Silk Road but also the lesser-known maritime routes that fostered rich exchanges between these two ancient civilizations. From Parthian-era silk textiles to exquisite Safavid-era blue-and-white porcelains commissioned by Shah Abbas himself, the exhibition paints a vivid picture of a friendship built on trade, artistry, and diplomacy.

Below is the full text of the interview in questions and answers:

Tell us about the number of objects on display in this exhibition, as well as some of its key highlights?

The Silk Legacy (aka Armaghan-e Abrisham) exhibition is mainly based on archaeological findings and artistic artifacts being kept at the National Museum of Iran and the Golestan Palace Museum. In total, around 90 objects are on display in this exhibition. These items reflect the long-standing cultural connections between Iran and China, which go back as far as 4,500 years. For instance, during Iran’s Bronze Age, there were already interactions with regions of ancient China.

However, the more well-known phase of Iran-China relations began through the route later known as the Silk Road, starting from the Parthian period. Some of the oldest artifacts we have on display are silk textiles discovered at the Germi archaeological site in Ardabil and the Qumis site near Damghan, both important Parthian-era locations. These finds, as presented by the National Museum of Iran, highlight the interactions between the Iranian and Chinese cultural spheres.

For example, in the Sasanian era, we see Sasanian coins that have been unearthed in multiple cities across China, clearly pointing to the wide commercial network and deep trade relations between the two civilizations.

Another highlight of the exhibition is the Sasanian silverware on display. These items were not just luxurious objects; they served a promotional purpose. The Sasanians sent such items to their neighbors and within their territories as symbols of prestige — essentially functioning like a billboard, promoting their cultural and political identity.

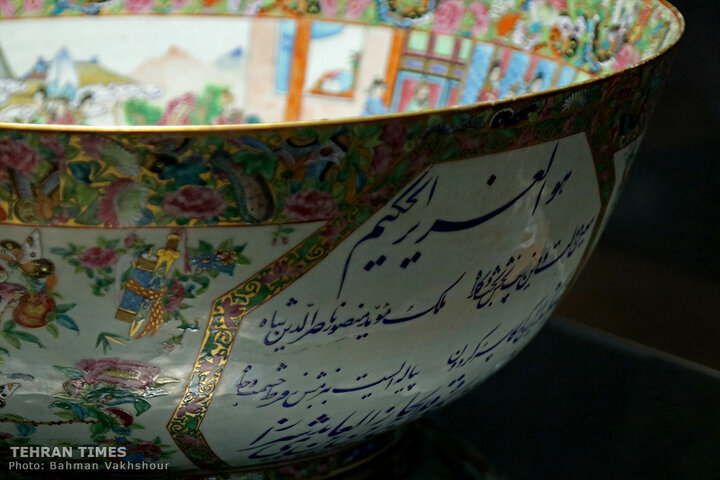

Interestingly, the exhibition also features a collection of blue-and-white Chinese porcelain that was specifically commissioned during the reign of Shah Abbas of the Safavid dynasty. These porcelains were custom-made in imperial kilns in China — not the ordinary kilns used for local or commercial production. These pieces were produced at the direct request of the Iranian king and were intended for Iran.

What makes them particularly remarkable is that some of these porcelains bear small inscriptions or seals with the name Shah Abbas, indicating that they were dedicated to the shrine complex of Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardabili, itself a UNSCO World Heritage.

In fact, the National Museum of Iran houses one of the largest collections of Chinese art in the region, including over 1,000 pieces such as blue-and-white porcelains, celadon wares, and other documents and objects related to this cultural exchange. It is an incredibly valuable and significant collection.

What were the main routes of connection between Iran and China, and what is your assessment of the nature of these cultural, economic, and commercial relations?

In addition to the overland routes, later known as the Silk Road(s), which linked us to China, we were also connected through the maritime Silk Road. In this exhibition, we showcase findings that confirm both types of routes. For example, Chinese coins and ceramics have been discovered at the port of Siraf in southern Iran. These include Chinese coins dating back to the early Islamic period, clearly demonstrating that we had extensive trade relations with China both over land and by sea.

When you study Chinese history and culture, you realize that when the Chinese referred to “the West,” they were often referring specifically to Iran. The Persian Empire was what lay to the west of China.

In contrast, for Iranians, the word “West” tends to evoke Europe and beyond, but in the Chinese mindset, Iran is the West. Another interesting point is that the Chinese have historically referred to Iran as “Pars” (Persia).

Culturally, economically, and commercially, the relationship between Iran and China has always been characterized by mutual cooperation and goodwill. China would transfer its wealth through the Iranian imperial corridor toward the Mediterranean and Europe, and these two great civilizations shared friendly, collaborative, and productive relations. The Silk Road was one of the key communication and trade routes connecting them.

If we look deeper into the history of these interactions, how far back do such cultural exchanges go?

The connection between the Iranian plateau and China may date back to prehistoric times, potentially even to the Paleolithic period. There is evidence to suggest that the two regions were in contact in very early eras.

Is there anything else you’d like to add about this exhibition or any future similar exhibitions?

As for the current exhibition, I would say it has the potential to be expanded on a larger scale, with more items and greater diversity. In the future, we could collaborate with other museums. For instance, Moqaddam Museum in Tehran and organize joint exhibitions. The Moqaddam Museum houses many valuable artifacts that could help portray, on a larger scale, the historical connections between Iran and China.

Many of these artifacts were either exchanged through trade or influenced by cultural interaction– that is, their designs and production techniques reflect the impact of the other side’s traditions and aesthetics. For example, we have celadon wares, blue-and-white porcelain, and other types of ceramics. Some researchers believe that the techniques used to make these objects were adopted from Chinese methods, although this remains a topic of scholarly debate. Nevertheless, it is clear that we had broad cultural interactions.

Interestingly, among the pieces Shah Abbas acquired for the Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardabili complex, not all were contemporary to the Ming dynasty of that time. He also purchased antique Chinese items, some of which date back two to three centuries earlier than his own era.

These artifacts are still preserved in the Sheikh Safi complex, and it’s noteworthy –even for Chinese scholars — that the Iranian collection contains Chinese pieces that were already considered historical antiques in their own time, with some over 100 years old when they were acquired.

Considering that Mr. Cong Peiwu, the Beijing’s ambassador to Tehran, along with a number of diplomats and Chinese citizens, attended the opening ceremony of this exhibition, how can this exhibition be represented in modern Chinese society, and how might it encourage them to visit Iran?

On the opening day, a group of Chinese visitors attended, including four journalists. They had already visited another exhibition at the National Museum, and as they were leaving, their attention was drawn to the Chinese-language labels of the Silk Legacy exhibition. They entered, showed great interest, and were genuinely engaged.

Exhibitions like this serve as a platform for cultural dialogue. They allow us to show that our connection with China is not something new or solely political — it’s a friendship that goes back over 2,000 years, and according to some sources, even 4,500 years. This is not a recent alliance; it’s an ancient relationship.

For Chinese visitors, it’s a fascinating and meaningful experience. They observe the artifacts with deep interest, and many express how moving it is to see an exhibition about their own heritage in another country. It gives them a sense of national pride.

Even now, when Chinese tourists visit the exhibition, I try to speak with them directly, and I find they are delighted to discover such historical and cultural connections between Iran and China.

At the National Museum of Iran in recent years, we’ve worked to present our museum’s global role. In fact, just a few days ago during my visit to China, I tried to emphasize that Iran is a safe country, one open to dialogue and cultural exchange.

As a senior cultural heritage expert, do you personally have a favorite object in the exhibition?

As the museum director and as a heritage specialist, it’s truly difficult for me to choose. For example, should I pick the lustreware tile with the dragon motif from Takht-e Soleyman, or the blue-and-white porcelain from the Sheikh Safi al-Din collection, which is registered on the UNESCO World Heritage List? Or perhaps the artifacts from Siraf, or the silver objects from Garmi and Qumis?

Each of these items tells a unique story and offers a different interpretation of Iran–China relations. Every one of them opens up a whole world of information about our historical ties.

Take the dragon motif, for instance, during the Ilkhanid period, it was prominently featured in Iranian architecture. Questions like this are hard to answer definitively, so I prefer not to single out any one object, as they are all important in their own right.

Given the current sanctions against Iran, are there any challenges in organizing international exhibitions in the country?

Yes, one of the main challenges in hosting international exhibitions in Iran today is insuring historical objects, which has become difficult due to sanctions. There are only a few specialized companies that provide insurance for such items, and some refuse to work with Iran under pressure from the sanctions regime.

However, we managed to resolve this issue with China, and were able to insure and exhibit the objects we previously sent there.

Over the past year, Iran has held exhibitions in several Chinese cities — such as “The Glory of Ancient Persia” and “Land of Kindness”. To what extent have these encouraged visitors to consider traveling to Iran?

Museum exhibitions are essentially a long-term investment in the future. For example, when a first-grade student in China visits the Splendor of Iran exhibition, they are introduced to the depth and richness of Iranian civilization. You’re not just engaging with the present. You’re investing in the next 80 years.

Just a few days ago, during an event at the Palace Museum in Beijing, as the museum director presented the centennial history of the institution, the first slide of the presentation featured the Splendor of Iran poster. Directors from various museums that had hosted the exhibition spoke about Iran’s ancient civilization and praised the warm public reception in China. In fact, in the first few days of the exhibition, all tickets were sold out in advance.

In conclusion, I can say that the world has a deep interest in Iran’s cultural heritage. People want to explore and understand this rich and ancient civilization.

AM

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: tehrantimes.com