Natalie GriceBBC Wales

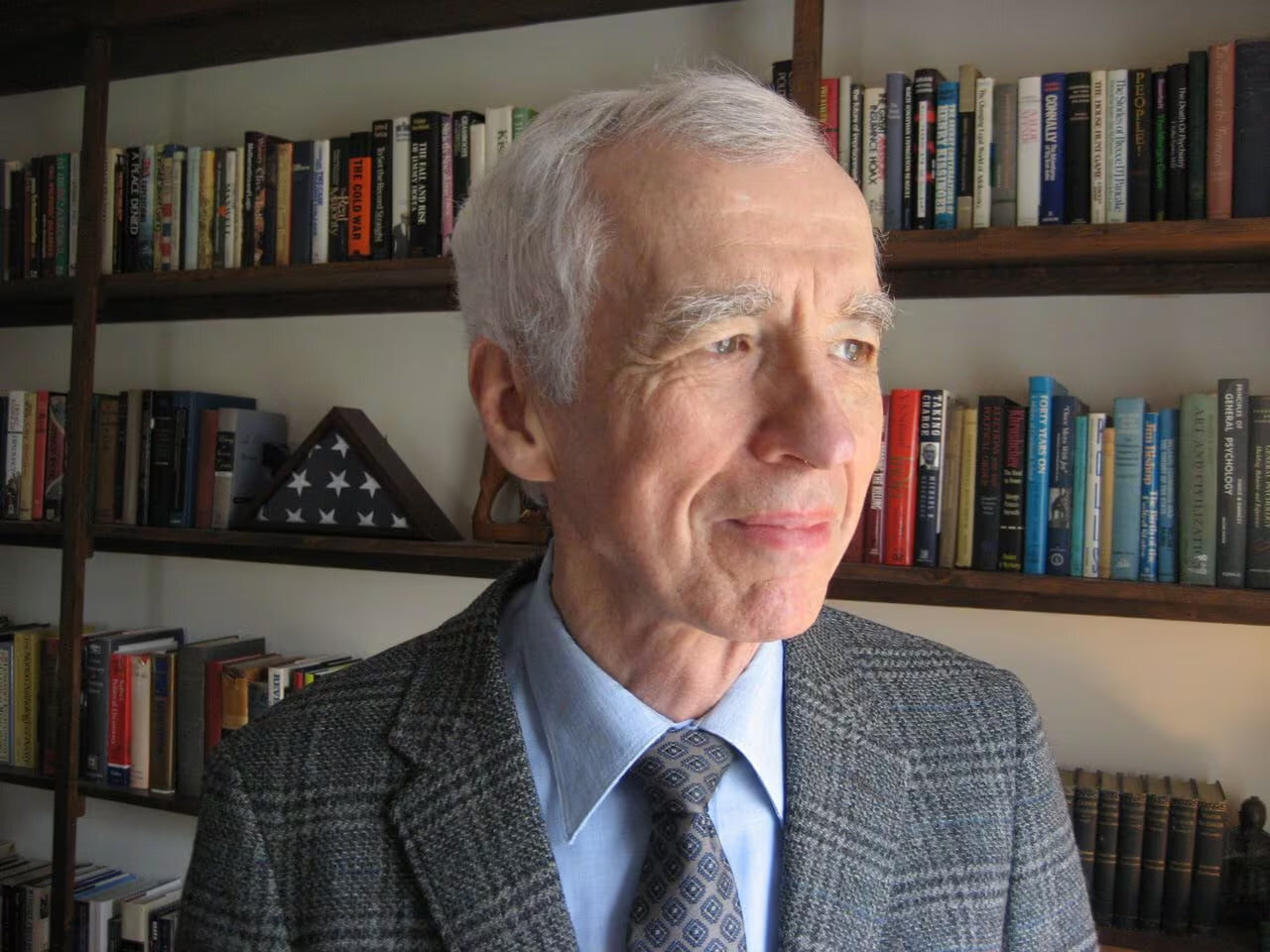

Mark Lewis

Mark Lewis“I remember standing in my cowshed and saying to my wife ‘one day I’m going to work for the Queen’ and we were surrounded by cow dung and stalls.”

Blacksmith Paul Dennis has come a long way from that cowpat-filled shed and – at the same time – not gone very far at all.

The unassuming 77-year-old has seen his work take him all over the world, while remaining firmly rooted in the Welsh hills.

His work has graced many notable buildings in the UK and beyond, from Windsor Castle and Westminster Abbey to the metalwork protecting the Crown Jewels in the Tower of London.

Closer to home, it is the gates he restored for Newport’s Tredegar House, featured in the opening credits to the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow, which proved pivotal in taking him on the road to royal commissions.

In a remote corner of the Bannau Brycheiniog, or Brecon Beacons, on fallow farmland hosting three sites of special scientific interest, Paul toils over his creations, surrounded by heat and metal.

His forge sits tucked away in one of the beacons’ hidden vales, only a few miles from the cowshed where he made that bold promise all those years ago.

Paul Dennis

Paul DennisHe is now celebrating 50 years of business with two big commissions.

One is to restore parts of Smithfield Market in the City of London in preparation for its conversion to the headquarters of the London Museum in 2026, and the other is building new gates for the Albany Mansions in London’s Piccadilly, home over the years to prime ministers, poets and playboys.

Paul comes from a long line of metalworkers going back “hundreds of years”.

His father was a farrier, his grandfather ran a company making wire machinery and his ancestors were nail makers.

Growing up on a farm near Ystrad Mynach in south Wales, there was no electricity, few comforts and self-reliance was necessary.

Aged 12, he began restoring cars and was fixing engines for local businesses.

After leaving school at 16 with no qualifications, Paul started working for his father but saw little future in shoeing horses and earning “the equivalent of 75p per horse and the chance to be kicked”.

Then a job came up that changed everything.

It was for Dyffryn Gardens, a Victorian county house outside Cardiff that is now a National Trust property.

“There were some gates for the rose gardens,” he said.

“I made these gates – I was 17 and they’re still there now. I thought, ‘this is it, it’s what I want to do’.”

Mark Lewis

Mark LewisIn his 20s, he set up his own business, honing his artistic skills along the way.

In 1983, he was given the Edney gates from Newport’s Tredegar House to restore – a job that would take two years as there was “about 15%” of them left.

“I found myself cleaning what’s left of the scrolls back and I started to get the style of the blacksmith, who was called William Edney,” said Paul.

“When you’re doing wrought iron, every blacksmith will do it slightly differently. I was determined I was going to do it exactly the same.

“I copied and copied and I managed to restore these gates back to what they look like now.”

Then came the call that changed everything.

Getty Images

Getty Images“I got an inquiry from Kensington Palace. I couldn’t believe it. I thought, ‘I’m never going to get this’.”

But he did.

The palace was home to Prince Charles and his first wife, Diana Princess of Wales, and the commission was for gates and railings separating the house from public gardens.

Paul remembers a difference of opinion with the royal couple about the look.

“They didn’t want [metal] flowers on the gates. It was me that covered them in flowers. They wanted to keep it plain and boring,” he said.

“I put in Yorkshire rose, Welsh daffodil and Irish shamrock. There’s crowns on the top and I put the wrong number of little dibbles, like diamonds, and they said, ‘oh that means he’s only an earl living here’.

“So I had to take the crowns back down and remake them to get the right number! I think it was 11.”

The gates were to later take a sombre centre stage in world history after being “covered in flowers when Princess Diana died”.

Paul Dennis

Paul DennisPaul was taken on by the Royal Household and Historic Royal Palaces for further commissions and remained working with them for 25 years.

“I got the amazing job for the Crown Jewels, to do all the metalwork package, all the protection for the Crown Jewels. That was absolutely terrifying at the time.”

Then came the call he had dreamed of all those years ago – to work for the Queen.

After the Windsor Castle fire in 1992, Paul got the “entire metalwork package” as part of the rebuild.

“I’ve still got a load of stuff from then that I’m not allowed to just sell, but it’s from St George’s Hall, all the nails and bits of furniture, bits of pieces which I use in restoration whenever I can.”

His career has taken him all around the world, from Middle Eastern palaces to the west coast of the USA.

But there have been a few hairy moments over the years.

Mark Lewis

Mark LewisPaul says casually: “I’ve worked for the mafia as well. I’ve been threatened to be killed twice. If I didn’t finish the stairs he was going to have me killed.

“He was very good in the end. He paid for everything and it went all right.”

His biggest job was for the Microsoft headquarters in Seattle: “I had to build the stairs here and then ship it over there and hope it fits.

“The whole of Seattle smells of coffee. I’m not a coffee drinker but the coffee was so amazing that I spent a week wide awake.”

At one stage he was employing 16 people but realised he had moved too far from what he actually loved – shaping metal.

So he reduced the business, now run by his son Gareth, to a manageable size with his son-in-law blacksmith and two daughters also involved.

Even after all these years, his enthusiasm has not dulled: “I didn’t think I’d be doing this now – I’m 77 and I thought ‘I’m not going to be doing this’ and yet I can’t stop.

“I’m as excited as I was in the 1960s.”

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: BBC