Angela Ferguson,BBC Walesand

Tomos Morgan,Wales correspondent

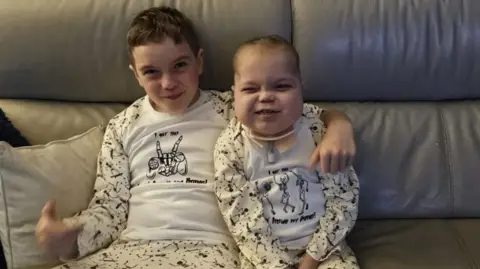

Family photo

Family photoAnna-Louise Bates has a special bond with little Roman, and when she says he has a “magic heart”, she isn’t exaggerating.

His heart is, in fact, her son Fraser’s, who died after being hit by a car 10 years ago on Saturday.

Mrs Bates lost her husband Stuart and Fraser, who was seven, after the accident while crossing the road in Talbot Green, Rhondda Cynon Taf.

It is also 10 years since a landmark organ donation law was introduced in Wales, aimed at increasing the number of donors.

One academic said it has had little effect, and Mrs Bates wants more to be done to break the taboo around donating, and help save children such as Roman.

Family photo

Family photoA charity set up by Mrs Bates, Believe Organ Donation Support, recently opened a memorial garden at Thornhill cemetery, Cardiff – it has fruit trees and grass mounds in the shape of organs such as a heart, liver and kidneys.

“I’ve got a really close bond with Roman’s mum now and she is incredibly supportive,” she said.

“We have just got this magic heart that joins us and for him to be there with what I call Roman’s heart… and he carries on with that joy and he battles so hard.”

Mrs Bates added it is “just phenomenal” Fraser had made such a huge difference through his organs being donated, and it proves “the heart really can go on”.

Roman’s mum Zoe described the agonising 10 month wait for a heart transplant, and the “emotional rollercoaster” as the family did not think it would happen right up until they received the call.

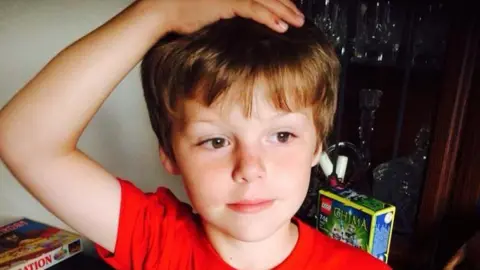

Anna-Louise Bates

Anna-Louise BatesWales was the first UK nation to adopt the “soft” opt-out legislation on 1 December 2015, which presumes a person’s consent to donate their organs when they die, unless they or their family have indicated otherwise.

The organ donor consent rate increased by about 15% during the first three years of the opt-out law, but dropped to its lowest level in a decade last year.

Mrs Bates believes stigma around the topic is an issue, and it is important people have what can be difficult conversations with loved-ones.

Her husband and son died just days after the legislation was introduced.

The Bates family, including their daughter Elizabeth, then aged three, had just been to a Christmas party.

IT programme manager Stuart, who was 43, was pronounced dead at the scene and Fraser was taken to hospital and later transferred to Bristol Children’s Hospital, where he died from head injuries.

Anna-Louise Bates

Anna-Louise BatesMrs Bates said she had spoken to her husband about him opting into the organ donor register less than three weeks earlier.

This conversation meant when she was approached about donating their organs “it was the one point in that 24-hour period that I didn’t have to think and I knew what they would have wanted me to do”.

“I am just so thankful that, even in that madness, I was able to fulfil what their wishes were,” she said.

Mrs Bates said the loss of her husband and son was “everyone’s worst nightmare” and it “still doesn’t feel real 10 years on”.

“One moment you have got your lovely family of four and then the next moment you are being asked these questions,” she added.

Mrs Bates said she had not expected to be asked for her consent for organ donation as she thought the “soft” opt-out legislation meant this was not needed.

She said she feared others thought the same and this meant less conversations were being had about the issue.

“What we really need to be saying to people is that, just because the law has changed, it doesn’t mean that this is as easy as you might think,” she said.

“These conversations desperately need to be had.

“I dread to think how I would have been or what emotions I would have gone through if I hadn’t had that conversation with Stu.”

This was part of the reason she set her charity up, describing organ donation as a “taboo subject” that people were “too scared to talk about it”.

Mrs Bates said children tended to see organ donation as “a gift of life”, in her experience, whereas adults possibly avoided talking about it as they associated it with death.

Anna-Louise Bates

Anna-Louise BatesThe organ donor consent rate has now fallen to its lowest level in a decade.

The NHS Blood and Transplant service (NHSBT) said presumed consent was not a silver bullet to closing the gap between donation and transplantation.

The Covid pandemic, fewer big media campaigns, limited resources and a possible distrust in the health service were some of the reasons given for the reduction in recent years.

Leah McLaughlin, a healthcare scientist at Bangor University, Gwynedd, said: “We also need more messages embedded in day-to-day life so it becomes more of a normal expected end of life care, which is what NHSBT is trying to do, but we do need the infrastructure to support those messages.”

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: BBC