Will GrantBBC Central America correspondent

Reuters

ReutersThe escalating tension between the US and Venezuela has led to the biggest military build-up in the Caribbean since the end of the Cold War.

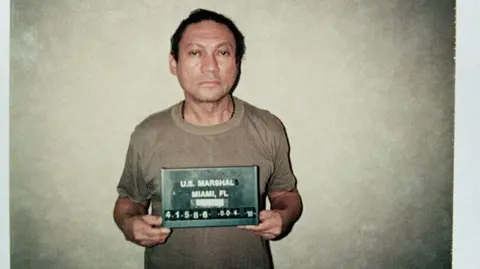

The last time so many US warships and troops were sent to the region was in 1989, when Washington removed Panama’s President Manuel Noriega – whom it accused of drug-trafficking – from office.

But the similarities between the two moments are outweighed by their differences.

On 16 December 1989, US Marine Lt Robert Paz was in the back of a Chevrolet Impala making his way to the Marriott Hotel in Panama City for dinner, just as US tensions with the Panamanian strongman were reaching boiling point.

When the car, which was carrying four US military personnel stationed in the country, reached a checkpoint of the Panamanian Defence Forces, six soldiers surrounded the vehicle.

Following an altercation, the Panamanians opened fire as it drove away, killing Paz. His death set in motion the US invasion of Panama four days later, on 20 December.

It remains the last major US incursion on foreign soil in the Americas.

By the end of what Washington dubbed “Operation Just Cause”, around 30,000 US troops had been mobilised, and Noriega had been forced from power and whisked to Miami to face trial on drug-smuggling charges.

The UN estimates around 500 Panamanian civilians were killed in the invasion. The US claims it was far fewer, while its critics say it was many more.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe invasion of Panama was also the last time there was a major US military build-up in the Caribbean on the level we are now seeing in the waters around Venezuela.

The parallels between the two moments are noticeable, but so too are the distinctions.

Firstly, the similarities. They may be separated by several decades but in each instance, an escalating war of words between Washington and a Latin American strongman after years of enmity led to a major US military deployment in the region.

Both involve allegations by Washington of presidential involvement in drug trafficking which have increased the internal pressure on a beleaguered Latin American leader.

In the cases of both Noriega and Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, the US government’s core argument is that they and their governments trafficked drugs.

Getty

GettyUltimately, the premise that the opposing president is, in essence, a drug lord has become the justification Washington has provided to the US public for all subsequent steps.

Both nations also have huge strategic importance – in the Panama Canal and Venezuela’s vast oil reserves – which raises the stakes considerably.

However, the differences are also stark.

The Cold War and the 21st Century are very different moments, and George HW Bush – who was at the helm in the US in 1989 – and Donald Trump are very different leaders.

Noriega had been a CIA asset for many years and was eventually convicted on some irrefutable evidence which ranged from financial records to the testimony of men who had run drug flights or laundered drug money in Panama for the Medellín Cartel. Even one of the cartel’s top leaders fingered Noriega as personally involved the illegal trade.

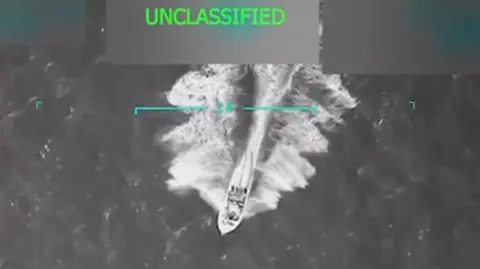

In the instance of Maduro, the Trump administration makes a direct link between go-fast boats which they have hit with lethal air strikes in the Caribbean and Maduro himself.

Washington’s accusation against Maduro is that he heads the Cartel of the Suns, a group which allegedly comprises members and ex-members of the Venezuelan top military brass.

But many drug war analysts question whether the Cartel of the Suns is a formal criminal group or rather a loose alliance of corrupt officials who have enriched themselves from the smuggling of drugs and natural resources via Venezuelan ports.

For their part, Maduro and his administration deny the existence of any such cartel, painting it as an unfounded “narrative” disseminated by Washington to dislodge them from power.

Reuters

Reuters“They have suddenly dusted off something called the Cartel of the Suns,” said Venezuela’s powerful Interior Minister, Diosdado Cabello. “They’ve never and will never be able to prove its existence because it doesn’t exist. It’s an imperialist invention,” he said last month.

There is, however, evidence of drug-trafficking within the first family in Venezuela.

Two of Maduro’s nephews through marriage were arrested in Haiti in a sting operation by the US Drug Enforcement Administration in 2015.

The children of the sister of Maduro’s wife were caught trying to smuggle 800kg of cocaine into the US.

Since known as the “narco-nephews”, Francisco Flores de Freitas and Efrain Antonio Campo Flores spent several years in a US prison before being returned to Venezuela in 2022 as part of a prisoner swap under the Biden administration.

The Trump administration has now hit the two alongside a third nephew, Carlos Erik Malpica Flores, with fresh sanctions.

Announcing the sanctions, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said: “Nicolás Maduro and his criminal associates in Venezuela are flooding the United States with drugs that are poisoning the American people.”

“Treasury is holding the regime and its circle of cronies and companies accountable for its continued crimes,” he added.

“Circle of cronies” sounds like the kind of language Washington used to describe Noriega’s government in the 1980s. A US Senate subcommittee report at the time called it “the hemisphere’s first narco-kleptocracy”.

Fast-forward 36 years and the key plank of the Trump administration’s strategy against Maduro hinges on the use of the term “narco-terrorism”.

It is controversial because of the broad scope of its legal definition. As early as 1987, the US Department of Justice defined narco-terrorism as “the involvement of terrorist organisations and insurgent groups in drug trafficking” which it noted “has become a problem with international implications”.

The issue in the Venezuelan context is the legal basis under international law for Washington’s latest actions as it pursues its stated aim of combating “narco-terrorism” in the Americas.

The Trump administration has said it is now engaged in a “non-international armed conflict” with the drug cartels and has justified its strikes on alleged narco-boats in the Caribbean under that definition.

Donald Trump/Truth Social

Donald Trump/Truth SocialThe Pentagon argues the vessels are valid targets under the rules of engagement. In recent days, though, serious questions have been raised over a second strike on an alleged drug-boat on 2 September, in which two survivors from an initial strike were killed.

The Trump administration has robustly defended itself against allegations that the second strike amounted to extrajudicial killings. However, the issue has not gone away nor have the calls for video footage of the strike – recently seen by senior lawmakers during a closed-door briefing to members of Congress – to be made public.

After initially suggesting he would have “no problem” with the footage of the follow-up strike being published, Trump said the decision was up to the Secretary of Defence, Pete Hegseth.

So far, the Pentagon has not published the video or the legal advice around the second strike, but the White House insists it was carried out “in accordance with the law of armed conflict”.

US-Venezuela tensions continue to escalate and intensify, not least following the seizure by US forces of a tanker filled with Venezuelan crude oil.

Trump has indicated that after the US take control of the airspace and the seas around Venezuela, all that is left is to control the land. Many are holding on to the hope that some kind of negotiated solution may yet be possible – although it is hard to see one which would satisfy both Maduro and the White House.

From examining the lesson of Panama, though, one thing remains clear: while this modern conflict may be less conventional than the invasion of Christmas 1989, the combustible situation in Venezuela has no less potential to be detonated by a single moment – like the killing of Lt Robert Paz in Panama – into something much larger.

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: BBC