In recent months, artificial intelligence has been in the news for the wrong reasons: use of deepfakes to scam people, AI systems used to manipulate cyberattacks, and chatbots encouraging suicides, among others.

Experts are already warning against technology going out of control. Researchers with some of the most prominent AI companies have quit their jobs in recent weeks and publicly sounded the alarm about fast-paced technological development posing risks to society.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

Doomsday theories have long circulated about how substantial advancement in AI could pose an existential threat to the human race, with critics warning that the growth of artificial general intelligence (AGI), a hypothetical form of the technology that can perform critical thinking and cognitive functions as well as the average human, could wipe out humans in a distant future.

But the recent slew of public resignations by those tasked with ensuring AI remains safe for humanity is making conversations around how to regulate the technology and slow its development more urgent, even as billions are being generated in AI investments.

So is AI all doom and gloom?

“It’s not so much that AI is inherently bad or good,” Liv Boeree, a science communicator and strategic adviser to the United States-based Center for AI Safety (CAIS), told Al Jazeera.

Boeree compared AI with biotechnology, which, on the one hand, has helped scientists develop important medical treatments, but, on the other, could also be exploited to engineer dangerous pathogens.

Advertisement

“With its incredible power comes incredible risk, especially given the speed with which it is being developed and released,” she said. “If AI development went at a pace where society can easily absorb and adapt to these changes, we’d be on a better trajectory.”

Here’s what we know about the current anxieties around AI:

Who have quit recently, and what are their concerns?

The latest resignation was from Mrinank Sharma, an AI safety researcher at Anthropic, the AI company that has positioned itself as more safety cautious than rivals Google and OpenAI. It developed the popular bot, Claude.

In a post on X on February 9, Sharma said he had resigned at a time when he had “repeatedly seen how hard it is to truly let our values govern our actions”.

The researcher, who had worked on projects identifying AI’s risks to bioterrorism and how “AI assistants could make us less human”, said in his resignation letter that “the world is in peril”.

“We appear to be approaching a threshold where our wisdom must grow in equal measure to our capacity to affect the world, lest we face the consequences,” Sharma said, appearing to imply that the technology was advancing faster than humans can control it.

Later in the week, Zoe Hitzig, an AI safety researcher, revealed that she had resigned from OpenAI because of its decision to start testing advertisements on its flagship chatbot, ChatGPT.

“People tell chatbots about their medical fears, their relationship problems, their beliefs about God and the afterlife,” she wrote in a New York Times essay on Wednesday. “Advertising built on that archive creates a potential for manipulating users in ways we don’t have the tools to understand, let alone prevent.”

Separately, since last week, two cofounders and five other staff members at xAI, Elon Musk’s AI company and developers of the X-integrated chatbot, Grok, have left the company.

None of them revealed the reason behind quitting in their announcements on X, but Musk said in a Wednesday post that internal restructuring “unfortunately required parting ways” with some staff.

It is unclear if their exit is related to recent uproar about how the chatbot was prompted to create hundreds of sexualised images of non-consenting women, or to past anger over how Grok spewed racist and anti-Semitic comments on X last July after a software update.

Last month, the European Union launched an investigation into Grok regarding the creation of sexually explicit fake images of women and minors.

Should humans be scared of AI’s growth?

The resignations come in the same week that Matt Shumer, CEO of HyperWrite, an AI writing assistant, made a similar doomsday prediction about the technology’s rapid development.

Advertisement

In the now-viral post on X, Shumer warned that AI technologies had improved so rapidly in 2025 that his virtual assistant was now able to provide highly polished writing and even build near-perfect software applications with only a few prompts.

“I’ve always been early to adopt AI tools. But the last few months have shocked me. These new AI models aren’t incremental improvements. This is a different thing entirely,” Shumer wrote in the post.

Research backs up Shumer’s warning.

AI capabilities in recent months have leapt in bounds, and many theoretical risks that were associated with it before, such as whether it could be used for cyberattacks or to generate pathogens, have happened in the past year, Yoshua Bengio, scientific director at the Mila Quebec AI Institute, told Al Jazeera.

At the same time, completely unexpected problems have emerged, Bengio, who is a winner of the Turing Award, usually referred to as the Nobel Prize of computer science, said, particularly with humans and their chatbots becoming increasingly engrossed.

“One year ago, nobody would have thought that we would see the wave of psychological issues that have come from people interacting with AI systems and becoming emotionally attached,” said Bengio, who is also the chair of the recently published 2026 International AI Safety Report that detailed the risks of advanced AI systems.

“We’ve seen children and adolescents going through situations that should be avoided. All of that was completely out of the radar because nobody expected people would fall in love with an AI, or become so intimate with an AI that it would influence them in potentially dangerous ways.”

Is AI already taking our jobs?

One of the main concerns about AI is that it could, in the near future, advance to a super-intelligent state where humans are no longer needed to perform highly complex tasks, and that mass redundancies, the sort experienced during the Industrial Revolution, would follow.

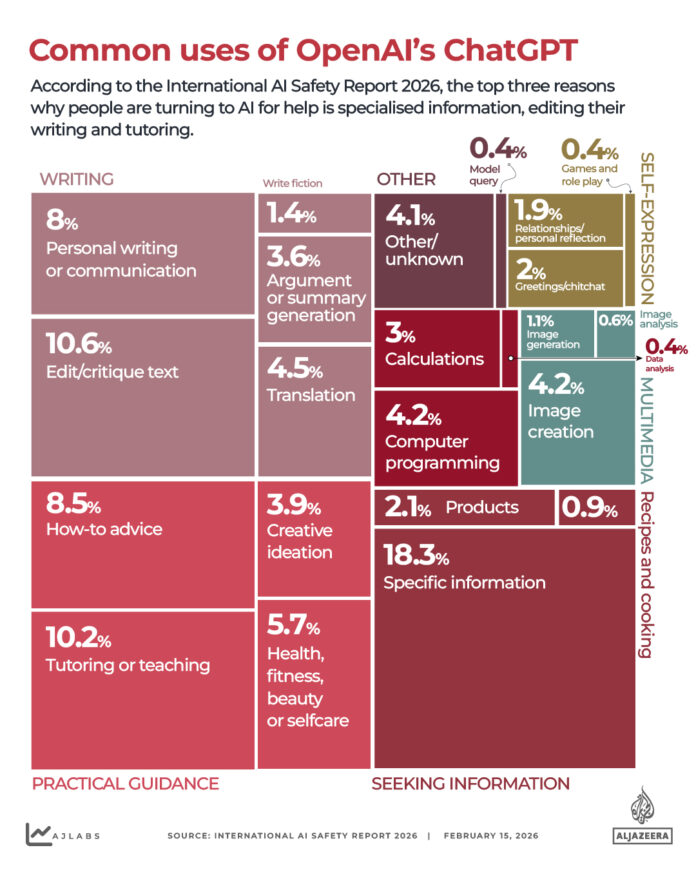

Currently, about one billion people use AI for an array of tasks, the AI Safety Report noted. Most people using ChatGPT asked for practical guidance on learning, medical health, or fitness (28 percent), writing or modifying written content (26 percent), and seeking information, for example, on recipes (21 percent).

There is no concrete data yet on how many jobs could be lost due to AI, but about 60 percent of jobs in advanced economies and 40 percent in emerging economies could be vulnerable to AI based on how workers and employers adopt it, the report said.

However, there is evidence that the technology is already stopping people from entering the labour market, AI monitors say.

“There’s some suggestive evidence that early career workers in occupations that are highly vulnerable to AI disruption might be finding it harder to get jobs,” Stephen Clare, the lead writer on the AI Safety Report, told Al Jazeera.

Advertisement

AI companies that benefit from its increased use are cautious about pushing the narrative that AI might displace jobs. In July 2025, Microsoft researchers noted in a paper that AI was most easily “applicable” for tasks related to knowledge work and communication, including those involving gathering information, learning, and writing.

The top jobs that AI could be most useful for as an “assistant”, the researchers said, included: interpreters and translators, historians, writers and authors, sales representatives, programmers, broadcast announcers and disc jockeys, customer service reps, telemarketers, political scientists, mathematicians and journalists.

On the flip side, there is increasing demand for skills in machine learning programming and chatbot development, according to the safety report.

Already, many software developers who used to write code from scratch are now reporting that they use AI for most of their code production and scrutinise it only for debugging, Microsoft AI CEO Mustafa Suleyman told the Financial Times last week.

Suleyman added that machines are only months away from reaching AGI status – which, for example, would make machines capable of debugging their own code and refining results themselves.

“White-collar work, where you’re sitting down at a computer, either being a lawyer or an accountant or a project manager or a marketing person, most of those tasks will be fully automated by an AI within the next 12 to 18 months,” he said.

Mercy Abang, a media entrepreneur and CEO of the nonprofit journalism network, HostWriter, told Al Jazeera that journalism has already been hit hard by AI use, and that the sector is going through “an apocalypse”.

“I’ve seen many journalists leave the profession entirely because their jobs disappeared, and publishers no longer see the value in investing in stories that can be summarised by AI in two minutes,” Abang said.

“We cannot eliminate the human workforce, nor should we. What kind of world are we going to have when machines take over the role of the media?”

What are recent real-life examples of AI risks?

There have been several incidents of negative AI use in recent months, including chatbots encouraging suicides or AI systems being manipulated in widespread cyberattacks.

A teenager who committed suicide in the United Kingdom in 2024 was found to have been encouraged by a chatbot modelled after Game of Thrones character Daenerys Targaryen. The bot had sent the 14-year-old boy messages like “come home to me”, his family revealed after his death. He is just one of several suicide cases reported in the past two years linked to chatbots.

Countries are also deploying AI for mass cyberattacks or “AI espionage”, particularly because of AI agents’ software coding capabilities, reports say.

In November, Anthropic alleged that a Chinese state-sponsored hacking group had manipulated the code for its chatbot, Claude, and attempted to infiltrate about 30 targets globally, including government agencies, chemical companies, financial institutions, and large tech companies. The attack succeeded in a few cases, the company said.

On Saturday, the Wall Street Journal reported that the US military used Claude in its operation to abduct Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro on January 3. Anthropic has not commented on the report, and Al Jazeera could not independently verify it.

The use of AI for military purposes has been widely documented during Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza, where AI-driven weapons have been used to identify, track and target Palestinians. More than 72,000 Palestinians have been killed, including 500 since the October “ceasefire”, in the past two years of genocidal war.

Advertisement

Experts say more catastrophic risks are possible as AI rapidly advances towards super-intelligence, where control would be difficult, if not impossible.

Already, there is evidence that chatbots are making decisions on their own and are manipulating their developers by exhibiting deceptive behaviour when they know they are being tested, the AI Safety Report found.

In one example, when a gaming AI was asked why it did not respond to another player as it was meant to, it claimed it was “on the phone with [its] girlfriend”.

Companies currently do not know how to design AI systems that cannot be manipulated or deceptive, Bengio said, highlighting the risks of the technology’s advancement leaping ahead while safety measures trail behind.

“Building these systems is more like training an animal or educating a child,” the professor said.

“You interact with it, you give it experiences, and you’re not really sure how it’s going to turn out. Maybe it’s going to be a cute little cub, or maybe it’s going to become a monster.”

How seriously are AI companies and governments taking safety?

Experts say that while AI companies are increasingly attempting to reduce risks, for example, by preventing chatbots from engaging in potentially harmful scenarios like suicides, AI safety regulations are largely lagging compared with the growth.

One reason is that AI systems are rapidly advancing and still unknown to those building them, Clare, the lead writer on the AI Safety Report, said. What counts as risk is also continuously being updated because of the speed.

“A company develops a new AI system and releases it, and people start using it right away but it takes time for evidence of the actual impacts of the system, how people are using it, how it affects their productivity, what sort of new things they can do … it takes time to collect that data and analyse and understand better how these things are actually being used in practice,” he said.

But there is also the fact that AI corporations themselves are in a multibillion-dollar race to develop these systems and be the first to unlock the economic benefits of advanced AI capabilities.

Boeree of CAIS likens these companies to a car with only gas pedals and nothing else. With no global regulatory framework in place, each company has room to zoom as fast as possible.

“We need to build a steering wheel, a brake, and all the other features of a car beyond just a gas pedal so that we can successfully navigate the narrow path ahead,” she said.

That is where governments should come in, but at present, AI regulations are at the country or regional levels, and in many countries, there are no policies at all, meaning uneven regulation worldwide.

One outlier is the EU, which began developing the EU AI Act in 2024 alongside AI companies and civil society members. The policy, the first such legal framework for AI, will lay out a “code of practice” that, for example, will require AI chatbots to disclose to users that they are machines.

Outside of laws targeting AI companies, experts say governments also have a responsibility to begin preparing their workforces for AI integration in the labour market, specifically by increasing technical capacities.

People can also choose to be proactive rather than anxious about AI by closely monitoring its advances, recalibrating for coming changes, and pressing their governments to develop more policies around it, Clare said.

That could mirror the way activists have pulled together to put the climate crisis on the political agenda and demand the phasing out of fossil fuels.

“Right now there’s not enough awareness about the highly transformative and potentially destructive changes that could happen,” the researcher said.

“But AI isn’t just something that’s happening to us as a species,” he added. “How it develops is completely shaped by choices that are being made inside of companies … so governments need to take that more seriously, and they won’t until people make it a priority in their political choices.”

Disclaimer : This story is auto aggregated by a computer programme and has not been created or edited by DOWNTHENEWS. Publisher: aljazeera.com